The IRS is having a sale!

Starting in 2010, and in every year after that, anyone willing to pay the income tax cost may convert all or part of their traditional pre-tax IRA’s to a Roth IRA. You will no longer be precluded from doing this if your modified Adjusted Gross Income exceeds $100,000 as is currently the case. And to kick off this new opportunity, they’re having a one-time sale on Roth-ification. A grand opening sale, if you will.

Here’s the deal. Let’s say you have a $500,000 traditional IRA, and you’d like to convert $200,000 of it to a Roth IRA. If you do that in 2009 or 2011 or later, the normal rules apply; normally, you would add that $200,000 to your taxable income in the year of the conversion and pay tax on it at your tax bracket for that year. More likely, with such a large amount of additional income you would end up crossing tax brackets and paying tax at some blended rate.

But in 2010, you can take advantage of the IRS’s one-time sale. Instead of adding $200,000 to your 2010 income, you have the option of splitting it in half and adding half to your 2011 income and half to your 2012 income.

What a deal! There’s two potential benefits to be gained here. First, there’s delay. You get to delay tax payment, which is always worth something. You can set aside the tax dollars you’ll owe, put them in a money market fund, and collect the interest for a while. The IRS is in effect giving you an interest-free loan for a year or two.

But wait. There’s more. Second, by spreading the taxable income—$200,000 in our example—over two years, you might reduce the portion of it that’s kicked up into a higher tax bracket and thereby actually reduce your overall tax bill. It’s Christmas in July! (Or April, actually.)

What about state tax? That depends on how your state figures its income tax. Many states, like New York and Georgia for instance, start their tax calculations with your federal Adjusted Gross Income and then fiddle around from there. In these states you’ll end up getting a similar state tax break, because your $200,000 will be split between your 2011 and 2012 federal Adjusted Gross Income. Unless your state legislature decides this particular situation ought to be handled differently.

So if you’ve concluded that Roth-ification of all or part of your IRA is a good idea for you, then doing it in 2010 might indeed be a very good idea.

Act now (actually next year). This offer won’t be repeated. Operators are standing by.

Saturday, February 28, 2009

Friday, February 27, 2009

Income: A Four Letter Word

The word “income” should be outlawed. Or if not outlawed, at least treated with same disdain and awkward silence that might greet an ethnic slur or the word “groovy.”

“Income” means so many different things—some precise, some vague and ill-defined—that its use can’t help but engender miscommunication. You mean one thing when you say “income,” I take it as something completely different, and—presto—miscommunication.

Or worse, even within the quiet confines of your own mind, using an ill-defined concept of “income” can lead to the capital crime of sloppy thinking.

Consider all the different meanings of income. Imagine you have a $5,000,000 pot of assets to retire on. Pretty nice thought, eh? You could live quite comfortably off that. Let’s say you decide to use the 4% Plan as described in January 13’s post (which I don’t particularly care for, but at least the arithmetic’s easy). So you pull out $200,000 to spend. What is your income?

• If that $5,000,000 is in a traditional IRA, and you take a $200,000 distribution, your tax accountant would say you have $200,000 of income. She’s thinking taxes and gross income.

• If you tell your accountant you have made $100,000 of non-deductible contributions to the IRA, she might say you have $196,000 of income. She's still thinking taxes, but now she’s thinking taxable income.

• If instead that $5,000,000 is in a trust Grandma left you, and the trust’s investments yielded, say, $100,000 of interest and dividends, your trustee would say you’ve gotten $100,000 of income and $100,000 of principal. He’s thinking traditional accounting income.

• If the trustee was a bit more modern, and applied his newfangled powers to redefine trust income, he might instead say that the entire $200,000 is income. He’s thinking modern trust accounting income.

• If you’ve decided to spend $200,000 because that’s the largest annual amount you think the pot will sustain for your whole lifetime, you might think that $200,000 is your income. You’re thinking of sustainable spending as income.

• If the $5,000,000 is in a managed investment account, which grew $400,000 in value during the year (not 2008 obviously), your investment advisor might say you had $400,000 of income, irrespective of how much you have chosen to spend. He’s thinking of investment performance as income.

• If, to get your allowance converted to cash, you had to sell $200,000 of appreciated stocks originally costing $50,000, your accountant might say you’ve got $150,000 of income. Again, being tax-oriented, she’s thinking of realized capital gain as income.

• If you took the whole $5,000,000 and bought an annuity paying you $300,000 per year for life, your insurance agent might say you’ve got $300,000 of income. She’s thinking of the annual annuity amount as income.

Eight different meanings of income, all valid within the appropriate context. But what really counts? Ask your grocer or your mortgage lender or your cable company. They just want to be paid in cash. They don’t care whether it’s income in any sense of the word. Really, income just doesn’t matter.

“Income” means so many different things—some precise, some vague and ill-defined—that its use can’t help but engender miscommunication. You mean one thing when you say “income,” I take it as something completely different, and—presto—miscommunication.

Or worse, even within the quiet confines of your own mind, using an ill-defined concept of “income” can lead to the capital crime of sloppy thinking.

Consider all the different meanings of income. Imagine you have a $5,000,000 pot of assets to retire on. Pretty nice thought, eh? You could live quite comfortably off that. Let’s say you decide to use the 4% Plan as described in January 13’s post (which I don’t particularly care for, but at least the arithmetic’s easy). So you pull out $200,000 to spend. What is your income?

• If that $5,000,000 is in a traditional IRA, and you take a $200,000 distribution, your tax accountant would say you have $200,000 of income. She’s thinking taxes and gross income.

• If you tell your accountant you have made $100,000 of non-deductible contributions to the IRA, she might say you have $196,000 of income. She's still thinking taxes, but now she’s thinking taxable income.

• If instead that $5,000,000 is in a trust Grandma left you, and the trust’s investments yielded, say, $100,000 of interest and dividends, your trustee would say you’ve gotten $100,000 of income and $100,000 of principal. He’s thinking traditional accounting income.

• If the trustee was a bit more modern, and applied his newfangled powers to redefine trust income, he might instead say that the entire $200,000 is income. He’s thinking modern trust accounting income.

• If you’ve decided to spend $200,000 because that’s the largest annual amount you think the pot will sustain for your whole lifetime, you might think that $200,000 is your income. You’re thinking of sustainable spending as income.

• If the $5,000,000 is in a managed investment account, which grew $400,000 in value during the year (not 2008 obviously), your investment advisor might say you had $400,000 of income, irrespective of how much you have chosen to spend. He’s thinking of investment performance as income.

• If, to get your allowance converted to cash, you had to sell $200,000 of appreciated stocks originally costing $50,000, your accountant might say you’ve got $150,000 of income. Again, being tax-oriented, she’s thinking of realized capital gain as income.

• If you took the whole $5,000,000 and bought an annuity paying you $300,000 per year for life, your insurance agent might say you’ve got $300,000 of income. She’s thinking of the annual annuity amount as income.

Eight different meanings of income, all valid within the appropriate context. But what really counts? Ask your grocer or your mortgage lender or your cable company. They just want to be paid in cash. They don’t care whether it’s income in any sense of the word. Really, income just doesn’t matter.

Labels:

Retirement Planning

Thursday, February 26, 2009

Hidden Tax Brackets

Yesterday’s post described the difficulty of figuring your tax bracket. It mentioned the concept of hidden tax brackets—places where the Tax Code causes you to lose a tax goody because of additional income, resulting in an effective marginal tax rate that’s way higher than what the published tables would have you believe. I thought it would be informative to provide an example.

Informative, yes. Useful, no. Because the intricacies of how these hidden brackets work make it difficult to predict them or plan around them. With that disclaimer, read on.

Example. George is single. He earns $55,000 in 2009 working for the New York Yankees, where he’s covered by a pension plan. George contributes $5,000 to a traditional individual retirement account. And that $5,000 is deductible, as explained in February 14’s post. George’s federal income tax works out to $6,350, after taking into account his IRA deduction, personal exemption and standard deduction. And he’s solidly ensconced in the 25% federal tax bracket.

Lucky George! The Yankees pay him an unexpected year-end bonus of $10,000! George guesses he’ll owe $2,500 federal tax on his year-end bonus because he’s in the 25% bracket. Wrong as usual, George! George is gob-smacked by a nasty hidden tax bracket. The extra $10,000 of income causes him to lose his $5,000 IRA deduction (again, see February 14’s post). Which in turn causes him to pay tax on $15,000 of income rather than $10,000. At his nominal 25% tax bracket, that’s $3,750 of tax. So his actual hidden tax bracket on the $10,000 bonus is 37.5%.

That’s a pretty high tax rate for a poor schlep like George, who’s not even the CEO of a failing bank.

Informative, yes. Useful, no. Because the intricacies of how these hidden brackets work make it difficult to predict them or plan around them. With that disclaimer, read on.

Example. George is single. He earns $55,000 in 2009 working for the New York Yankees, where he’s covered by a pension plan. George contributes $5,000 to a traditional individual retirement account. And that $5,000 is deductible, as explained in February 14’s post. George’s federal income tax works out to $6,350, after taking into account his IRA deduction, personal exemption and standard deduction. And he’s solidly ensconced in the 25% federal tax bracket.

Lucky George! The Yankees pay him an unexpected year-end bonus of $10,000! George guesses he’ll owe $2,500 federal tax on his year-end bonus because he’s in the 25% bracket. Wrong as usual, George! George is gob-smacked by a nasty hidden tax bracket. The extra $10,000 of income causes him to lose his $5,000 IRA deduction (again, see February 14’s post). Which in turn causes him to pay tax on $15,000 of income rather than $10,000. At his nominal 25% tax bracket, that’s $3,750 of tax. So his actual hidden tax bracket on the $10,000 bonus is 37.5%.

That’s a pretty high tax rate for a poor schlep like George, who’s not even the CEO of a failing bank.

Labels:

Financial Projections,

Roth Savings,

Savings Buckets

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

A Word or Two About Tax Rates

Yesterday’s post and a number of prior posts somewhat facilely refer to your tax bracket—both current and future. Just what do I mean by tax bracket? It's time to enter that heart of darkness.

When you are trying to decide between two retirement planning strategies—how much to save, how much to spend, to Roth or not to Roth, which savings bucket to spend first, in which savings bucket to house your stocks, etc.—it often becomes necessary to guess at, and compare, your marginal tax brackets. “Marginal” means the tax bracket affecting your top dollar of income, rather than the average tax rate on all of your income. They’re not the same because we have a progressive tax system.

(A brief aside: “Progressive” means the tax rate gets higher as your income increases, as with the federal income tax. “Regressive” means the rate gets lower as your income increases, as with the Social Security tax [6.2% on the first $106,800 of compensation, 0% on the rest]. But these words are really loaded. “Progressive” sounds so modern, advanced and forward-thinking. “Regressive” sounds like you’re a troglodyte. But no value judgments are intended. The words just describe how the rates vary with the thing that's taxed, income in this case.)

Example. Mary is single and earns $150,000 as a TV news producer. She uses the standard deduction, and claims just herself as a personal exemption. Her 2009 federal income tax totals $33,102, so her overall average tax rate is 22%. But her marginal tax bracket increases with each tranche of income. The first slice of $9,350 of income is taxed at 0% (representing her personal exemption and standard deduction). The next $8,350 is taxed at 10%; then $25,600 at 15%; $48,300 at 25%; and the balance ($58,400) at 28%. Mary’s marginal tax bracket is 28%. So any moves she makes—to reduce or increase her taxed income—either saves or increases her tax by 28%. Sort of. Read on.

Often things are not so simple. Here are some of the complications you’ll run into as you try to figure your marginal tax rate.

• Crossing brackets. A big move might cause you to shift—up or down—from one bracket to the next. So some of your income is at one marginal tax bracket and some at a different one. For example, converting a large traditional IRA to a Roth IRA can easily cause you to straddle two brackets.

• Alternative Minimum Tax. If you have large deductions that are classified as “tax preferences” (such as state and local taxes) then you might be paying Alternative Minimum Taxes, in which case your marginal tax bracket becomes 26% or 28% regardless of what the regular tax rate tables say.

• State income tax. If your state has an income tax, your marginal state tax rate should be added to your marginal federal tax rate to figure your effective tax bracket. In our example, Mary lives in Minnesota, and figures her marginal state tax rate is 7.85%, making her total marginal tax bracket 35.85%.

• Effect of state tax on federal income tax. If Mary itemizes her deductions, then her state tax reduces her federal tax. So her effective marginal tax bracket would then be 33.65%. Unless she’s paying Alternative Minimum Tax. Oy.

• Hidden tax brackets. The federal tax code is just full of hidden tax brackets. Various tax deductions , credits and other such goodies are available only to those with lower income, and then get phased out for those with higher income. If you are within these phase-out ranges—which vary from one goodie to the next—then you are actually subject to a higher hidden tax bracket, as you lose the benefit of a deduction or credit. Gotcha!

• Capital gains. Some income—notably long-term capital gain—is subject to favorable tax treatment, resulting in a lower tax bracket for that type of income.

The message here is that it’s massively complex just figuring what tax bracket you’re in today, even after you’ve completed your tax return. And so what about projecting your bracket 20 years into the future? Forget about precision. Just take your best shot at an educated guess.

The horror; the horror!

When you are trying to decide between two retirement planning strategies—how much to save, how much to spend, to Roth or not to Roth, which savings bucket to spend first, in which savings bucket to house your stocks, etc.—it often becomes necessary to guess at, and compare, your marginal tax brackets. “Marginal” means the tax bracket affecting your top dollar of income, rather than the average tax rate on all of your income. They’re not the same because we have a progressive tax system.

(A brief aside: “Progressive” means the tax rate gets higher as your income increases, as with the federal income tax. “Regressive” means the rate gets lower as your income increases, as with the Social Security tax [6.2% on the first $106,800 of compensation, 0% on the rest]. But these words are really loaded. “Progressive” sounds so modern, advanced and forward-thinking. “Regressive” sounds like you’re a troglodyte. But no value judgments are intended. The words just describe how the rates vary with the thing that's taxed, income in this case.)

Example. Mary is single and earns $150,000 as a TV news producer. She uses the standard deduction, and claims just herself as a personal exemption. Her 2009 federal income tax totals $33,102, so her overall average tax rate is 22%. But her marginal tax bracket increases with each tranche of income. The first slice of $9,350 of income is taxed at 0% (representing her personal exemption and standard deduction). The next $8,350 is taxed at 10%; then $25,600 at 15%; $48,300 at 25%; and the balance ($58,400) at 28%. Mary’s marginal tax bracket is 28%. So any moves she makes—to reduce or increase her taxed income—either saves or increases her tax by 28%. Sort of. Read on.

Often things are not so simple. Here are some of the complications you’ll run into as you try to figure your marginal tax rate.

• Crossing brackets. A big move might cause you to shift—up or down—from one bracket to the next. So some of your income is at one marginal tax bracket and some at a different one. For example, converting a large traditional IRA to a Roth IRA can easily cause you to straddle two brackets.

• Alternative Minimum Tax. If you have large deductions that are classified as “tax preferences” (such as state and local taxes) then you might be paying Alternative Minimum Taxes, in which case your marginal tax bracket becomes 26% or 28% regardless of what the regular tax rate tables say.

• State income tax. If your state has an income tax, your marginal state tax rate should be added to your marginal federal tax rate to figure your effective tax bracket. In our example, Mary lives in Minnesota, and figures her marginal state tax rate is 7.85%, making her total marginal tax bracket 35.85%.

• Effect of state tax on federal income tax. If Mary itemizes her deductions, then her state tax reduces her federal tax. So her effective marginal tax bracket would then be 33.65%. Unless she’s paying Alternative Minimum Tax. Oy.

• Hidden tax brackets. The federal tax code is just full of hidden tax brackets. Various tax deductions , credits and other such goodies are available only to those with lower income, and then get phased out for those with higher income. If you are within these phase-out ranges—which vary from one goodie to the next—then you are actually subject to a higher hidden tax bracket, as you lose the benefit of a deduction or credit. Gotcha!

• Capital gains. Some income—notably long-term capital gain—is subject to favorable tax treatment, resulting in a lower tax bracket for that type of income.

The message here is that it’s massively complex just figuring what tax bracket you’re in today, even after you’ve completed your tax return. And so what about projecting your bracket 20 years into the future? Forget about precision. Just take your best shot at an educated guess.

The horror; the horror!

Labels:

Financial Projections,

Roth Savings,

Savings Buckets

Tuesday, February 24, 2009

How Age and Tax Rate Affect the Roth Decision

In a few recent posts, I have talked about the long-term benefit of Roth-ifying your retirement funds. But is it a good idea for everyone? Certainly not. It’s hard to assess all the factors and uncertainties that go into the decision. But probably the two most critical factors are Time and Tax Rate: How many years until your retirement? How large will your future income tax rate be compared to your current tax rate?

How do these factors impact the Roth decision? Here’s a little thought experiment. Picture Riley. He’s got $10,000 in a traditional IRA and $10,000 in an ordinary taxable investment account. Should he spend some of the dollars in his taxable account to convert the $10,000 IRA into a $10,000 Roth IRA? That depends on how many years Riley has until he retires and his future tax rate. The chart below shows the benefit (or detriment) of the Roth conversion, as measured by the increase (or decrease) in Riley’s future annual after-tax retirement spending generated by his $20,000.

Riley is currently—during his working years—in the 30% tax bracket. The projections below indicate that he might still enjoy some advantage from Roth-ifying his IRA, although a shrinking one, if he expects to be in a lower tax bracket during his retirement years.

Here are the assumptions that went into the figures in the chart.

• Riley’s current tax rate is 30%, so it costs $3,000 to convert his IRA to a Roth.

• Riley is in the 30% tax bracket during his working years.

• Riley’s IRA (traditional or Roth) earns 6% per year during his working years.

• Riley’s taxable account earns 6% during his working years, but keeps only 4.8% after tax.

• Riley spends his two accounts by amortizing them over a 25-year retirement period.

• Riley’s IRA (traditional or Roth) earns 5% per year during his retirement years (when his investments get more conservative).

• Riley’s taxable account earns a fraction of that 5% after tax. To estimate that percentage, I used the following formula:

5% - (2/3) x Tax Rate x 5%

See February 3’s post for the reasons behind the 2/3 fudge factor.

• Riley's assumed number of remaining working years are shown in the top row of the chart below.

• Riley's assumed tax rate during his retirement years are shown in the left-hand column of the chart below.

How do these factors impact the Roth decision? Here’s a little thought experiment. Picture Riley. He’s got $10,000 in a traditional IRA and $10,000 in an ordinary taxable investment account. Should he spend some of the dollars in his taxable account to convert the $10,000 IRA into a $10,000 Roth IRA? That depends on how many years Riley has until he retires and his future tax rate. The chart below shows the benefit (or detriment) of the Roth conversion, as measured by the increase (or decrease) in Riley’s future annual after-tax retirement spending generated by his $20,000.

Riley is currently—during his working years—in the 30% tax bracket. The projections below indicate that he might still enjoy some advantage from Roth-ifying his IRA, although a shrinking one, if he expects to be in a lower tax bracket during his retirement years.

Here are the assumptions that went into the figures in the chart.

• Riley’s current tax rate is 30%, so it costs $3,000 to convert his IRA to a Roth.

• Riley is in the 30% tax bracket during his working years.

• Riley’s IRA (traditional or Roth) earns 6% per year during his working years.

• Riley’s taxable account earns 6% during his working years, but keeps only 4.8% after tax.

• Riley spends his two accounts by amortizing them over a 25-year retirement period.

• Riley’s IRA (traditional or Roth) earns 5% per year during his retirement years (when his investments get more conservative).

• Riley’s taxable account earns a fraction of that 5% after tax. To estimate that percentage, I used the following formula:

5% - (2/3) x Tax Rate x 5%

See February 3’s post for the reasons behind the 2/3 fudge factor.

• Riley's assumed number of remaining working years are shown in the top row of the chart below.

• Riley's assumed tax rate during his retirement years are shown in the left-hand column of the chart below.

Labels:

Roth Savings,

Savings Buckets

Monday, February 23, 2009

Tax-Free Conversion of Non-Deductible IRA Contributions to Roth IRA

In yesterday’s post, I described how you figure the tax cost of converting a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA when you’ve got some non-deductible contributions in the traditional IRA. I used an example of an $80,000 traditional IRA with $10,000 of non-deductible contributions.

Wouldn’t it be great if you could just convert the $10,000 of non-deductible contributions to a Roth IRA, and pay no tax for the privilege of doing so? Well, maybe you can. Here’s a little trick that might work for you. Read on.

If your employer maintains a tax-favored retirement plan, such as a 401(k) plan or a 403(b) plan, and that plan accepts rollovers from IRAs, then before you do your Roth conversion, you roll over the taxable portion of your traditional IRA to your employer’s plan, $70,000 in our example. In fact, you’re not even allowed to rollover your $10,000 of non-deductible IRA contributions to an employer plan. What does that leave you with? A $10,000 traditional IRA, all of which is considered your own non-deductible contributions. You can convert the whole thing to a Roth IRA without paying any income tax for the privilege of doing so! What a country!

Here’s a couple of caveats about the foregoing trick:

• It only works if you qualify for a Roth IRA conversion, i.e., $100,000 or less Adjusted Gross Income in 2009. Or wait until 2010, when the AGI limit goes away.

• It only works if your employer’s plan accepts rollovers from IRAs. Some do, some don't.

• You end up with most of your IRA money in your employer’s plan, subject to its investment and distribution restrictions, as described in February 11’s post and February 18’s post.

• While your retirement money is in your employer’s plan, you won’t be able to Roth-ificate it until you are able to roll it over back into an IRA.

But if you can get over these hurdles, you end up moving your non-deductible IRA contributions into a better savings bucket. Take that, IRS!

Wouldn’t it be great if you could just convert the $10,000 of non-deductible contributions to a Roth IRA, and pay no tax for the privilege of doing so? Well, maybe you can. Here’s a little trick that might work for you. Read on.

If your employer maintains a tax-favored retirement plan, such as a 401(k) plan or a 403(b) plan, and that plan accepts rollovers from IRAs, then before you do your Roth conversion, you roll over the taxable portion of your traditional IRA to your employer’s plan, $70,000 in our example. In fact, you’re not even allowed to rollover your $10,000 of non-deductible IRA contributions to an employer plan. What does that leave you with? A $10,000 traditional IRA, all of which is considered your own non-deductible contributions. You can convert the whole thing to a Roth IRA without paying any income tax for the privilege of doing so! What a country!

Here’s a couple of caveats about the foregoing trick:

• It only works if you qualify for a Roth IRA conversion, i.e., $100,000 or less Adjusted Gross Income in 2009. Or wait until 2010, when the AGI limit goes away.

• It only works if your employer’s plan accepts rollovers from IRAs. Some do, some don't.

• You end up with most of your IRA money in your employer’s plan, subject to its investment and distribution restrictions, as described in February 11’s post and February 18’s post.

• While your retirement money is in your employer’s plan, you won’t be able to Roth-ificate it until you are able to roll it over back into an IRA.

But if you can get over these hurdles, you end up moving your non-deductible IRA contributions into a better savings bucket. Take that, IRS!

Labels:

Roth Savings,

Savings Buckets

Sunday, February 22, 2009

Roth Conversion of Non-Deductible IRAs

In a number of posts, I have plugged the tax benefits of Roth IRAs. And in February 15’s post, I extolled the virtues of a non-deductible IRA when a deduction is unavailable. Today I amalgamate them. What if you want to convert a non-deductible IRA to a Roth IRA?

First, of course, you have to determine if you’re allowed to. February 10’s post pointed out that in 2009, you can do this only if your Adjusted Gross Income is $100,000 or less. But in 2010 and thereafter, that requirement disappears. Poof! It’s gone! And of course you generally have to pay income tax on the amount converted.

But if you’ve made non-deductible contributions to your traditional IRA, you don’t have to pay income tax on that portion. You paid tax going in, so you don’t have to pay it again. No double tax. Here’s an example. Let’s say your only IRA is worth $80,000 and over the years your aggregate non-deductible contributions have totaled $10,000. In tax jargon, $10,000 is your tax basis in the IRA. (You can find this number on your most recently filed Form 8606.) If you convert the entire IRA to a Roth IRA, you’ll have to pay tax on $70,000 (= $80,000 - $10,000).

But what if you convert only a portion of your IRA to a Roth IRA, e.g., because you can’t afford to pay tax on the whole thing? Then you recover a pro-rata portion of your tax basis. For example, if you convert $20,000 of your $80,000 IRA to a Roth IRA, that’s 25% of the total. So you recover $2,500 of your $10,000 tax basis, and pay tax on $17,500 (=$20,000 - $2,500). You then have $7,500 of basis left in your traditional IRA to recover tax-free in later years.

What if you’ve got more than one traditional IRA? In figuring the portion that’s tax-free, the IRS makes you aggregate all your traditional IRAs (but not your employer plans or Roth IRAs) and all your non-deductible contributions. So it doesn’t help to try to isolate your non-deductible contributions in one small IRA. The IRS is on to your little tricks!

But tomorrow I’ll describe a little trick that can work. Meet you back here about the same time tomorrow.

First, of course, you have to determine if you’re allowed to. February 10’s post pointed out that in 2009, you can do this only if your Adjusted Gross Income is $100,000 or less. But in 2010 and thereafter, that requirement disappears. Poof! It’s gone! And of course you generally have to pay income tax on the amount converted.

But if you’ve made non-deductible contributions to your traditional IRA, you don’t have to pay income tax on that portion. You paid tax going in, so you don’t have to pay it again. No double tax. Here’s an example. Let’s say your only IRA is worth $80,000 and over the years your aggregate non-deductible contributions have totaled $10,000. In tax jargon, $10,000 is your tax basis in the IRA. (You can find this number on your most recently filed Form 8606.) If you convert the entire IRA to a Roth IRA, you’ll have to pay tax on $70,000 (= $80,000 - $10,000).

But what if you convert only a portion of your IRA to a Roth IRA, e.g., because you can’t afford to pay tax on the whole thing? Then you recover a pro-rata portion of your tax basis. For example, if you convert $20,000 of your $80,000 IRA to a Roth IRA, that’s 25% of the total. So you recover $2,500 of your $10,000 tax basis, and pay tax on $17,500 (=$20,000 - $2,500). You then have $7,500 of basis left in your traditional IRA to recover tax-free in later years.

What if you’ve got more than one traditional IRA? In figuring the portion that’s tax-free, the IRS makes you aggregate all your traditional IRAs (but not your employer plans or Roth IRAs) and all your non-deductible contributions. So it doesn’t help to try to isolate your non-deductible contributions in one small IRA. The IRS is on to your little tricks!

But tomorrow I’ll describe a little trick that can work. Meet you back here about the same time tomorrow.

Labels:

Roth Savings,

Savings Buckets

Saturday, February 21, 2009

Figuring Substantially Equal Periodic Payments

Yesterday I described a way to avoid the 10% penalty tax on distributions from an IRA before age 59-1/2 by taking “substantially equal periodic payments.” Today’s post describes how to figure your distributions to meet this exception. Basically, the IRS has approved three methods for calculating “substantially equal” distributions.

Required Minimum Distribution method. Under this method, you determine your annual distributions by dividing your account balance by your remaining life expectancy. To get your life expectancy, you have the option of using (i) your single life expectancy, or (ii) the joint life expectancy of you and your beneficiary, or (iii) a table created by the IRS called the Uniform Lifetime Table. These three tables can be found in the appendix to IRS Publication 590, here:

http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p590.pdf

Once you select one of the three tables, you must stick with it. Each year you redetermine the appropriate life expectancy by going back to the selected table and getting a new divisor based on your attained age or ages in that year. The Required Minimum Distribution method results in a relatively low initial distribution, which then tends to grow over the years.

Life expectancy amortization method. Under this method, you determine an annual distribution by amortizing the IRA’s current value over a life expectancy. This method results in a fixed annual distribution which doesn’t change from year to year. You can do the amortization calculation using a financial calculator. In doing the calculation, you may get your life expectancy from one of the three tables described above; and you may choose any interest rate that does not exceed 120% of a rate published monthly by the IRS (called the federal mid-term rate) for either of the two months preceding the month your distributions begin. The IRS-published rates can be found on their website here:

http://www.irs.gov/app/picklist/list/federalRates.html

Mortality table method. Under this method, you determine an annual distribution by dividing your IRA balance by an annuity factor to be derived from an actuarial mortality table published by the IRS. Like the Life Expectancy Amortization method, this method results in a fixed amount which does not change from year to year. The services of an actuary are needed, making this method inconvenient.

The IRS has approved other methods for determining substantially equal periodic payments from an IRA, but only in private letter rulings, on which you may not rely (as time goes by). So if you act on the advice given in the ruling, you do so at your own risk.

In yesterday’s post, I mentioned that once you start on these distributions, you may not deviate from them without incurring substantial penalties. But here’s an exception: If you have been calculating your periodic distributions under either the Life Expectancy Amortization method or the Mortality Table method (both of which result in a fixed distribution), you are allowed to make a one-time switch to the Required Minimum Distribution method (but not back again) without incurring a penalty recapture tax.

Now that you know how to take IRA distributions before age 59-1/2 without penalty, let me ask you this: Why are you doing this?

Required Minimum Distribution method. Under this method, you determine your annual distributions by dividing your account balance by your remaining life expectancy. To get your life expectancy, you have the option of using (i) your single life expectancy, or (ii) the joint life expectancy of you and your beneficiary, or (iii) a table created by the IRS called the Uniform Lifetime Table. These three tables can be found in the appendix to IRS Publication 590, here:

http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p590.pdf

Once you select one of the three tables, you must stick with it. Each year you redetermine the appropriate life expectancy by going back to the selected table and getting a new divisor based on your attained age or ages in that year. The Required Minimum Distribution method results in a relatively low initial distribution, which then tends to grow over the years.

Life expectancy amortization method. Under this method, you determine an annual distribution by amortizing the IRA’s current value over a life expectancy. This method results in a fixed annual distribution which doesn’t change from year to year. You can do the amortization calculation using a financial calculator. In doing the calculation, you may get your life expectancy from one of the three tables described above; and you may choose any interest rate that does not exceed 120% of a rate published monthly by the IRS (called the federal mid-term rate) for either of the two months preceding the month your distributions begin. The IRS-published rates can be found on their website here:

http://www.irs.gov/app/picklist/list/federalRates.html

Mortality table method. Under this method, you determine an annual distribution by dividing your IRA balance by an annuity factor to be derived from an actuarial mortality table published by the IRS. Like the Life Expectancy Amortization method, this method results in a fixed amount which does not change from year to year. The services of an actuary are needed, making this method inconvenient.

The IRS has approved other methods for determining substantially equal periodic payments from an IRA, but only in private letter rulings, on which you may not rely (as time goes by). So if you act on the advice given in the ruling, you do so at your own risk.

In yesterday’s post, I mentioned that once you start on these distributions, you may not deviate from them without incurring substantial penalties. But here’s an exception: If you have been calculating your periodic distributions under either the Life Expectancy Amortization method or the Mortality Table method (both of which result in a fixed distribution), you are allowed to make a one-time switch to the Required Minimum Distribution method (but not back again) without incurring a penalty recapture tax.

Now that you know how to take IRA distributions before age 59-1/2 without penalty, let me ask you this: Why are you doing this?

Labels:

Savings Buckets

Friday, February 20, 2009

Substantially Equal Periodic Payments Exception to the 10% Penalty

Yesterday’s post was sort of a catalogue of exceptions to the 10% penalty tax on distributions from tax-favored retirement plans before age 59-1/2. Only one of those exceptions is within your control: Substantially equal periodic payments. Sometimes jargon-loving financial planners call this the “72(t) exception.”

Today’s post provides an overview of the exception; tomorrow I will go into how you actually calculate distributions that qualify. So here goes the overview.

You may take distributions from a tax-favored retirement plan at any time, without incurring the 10% penalty tax, if the distributions are structured as a series of distributions and the series consists of substantially equal periodic payments. These are rather strict requirements. And you will find that this technique for avoiding a penalty tax will not result in a large immediate distribution, so it will not be suitable if you’re looking to gain immediate access to a large chunk of your IRA. Rather, it can work well—if somewhat inflexibly—if you’re under 59-1/2 and you’re looking to spread your distributions over your lifetime.

Triggering event. If the distributions come from a traditional or Roth Individual Retirement Account, they do not have to be triggered by any particular event. You may start them at any time and any age. However, if they come out of an employer plan, to qualify they must begin after you have separated from service with the employer. Since most employer plans do not offer participants the option to take distributions in flexible ways, you are unlikely to be applying this exception to employer plan distributions. More likely, if you utilize this distribution method, it will be from an IRA.

Frequency of distributions. To qualify, the series of distributions must be periodic, no less frequently than annually. A series of monthly or quarterly distributions may also qualify.

Term of distributions. To qualify, the series must be calculated to occur over one of the following terms:

• Your life expectancy (more on this tomorrow)

• The joint life expectancy of you and your beneficiary

• Your actual lifetime (i.e., in the form of a life annuity)

• The actual lifetime of you and your beneficiary (i.e., in the form of a joint and survivor annuity).

Separate IRAs. In private letter rulings, the IRS has been liberal in allowing someone with two IRAs to calculate substantially equal periodic payments separately for one of the IRAs, while leaving the other IRA untouched; or alternatively, aggregating the IRAs for purposes of calculating the distributions.

Modification of periodic payments. Now, here’s the bad news. Once you start taking substantially equal periodic payments from an IRA, you should continue doing so at least until age 59-1/2, or, if later, five years from the initial distribution. If you modify your series of distributions before age 59-1/2 or five years—including ceasing your distributions—the IRS will recapture the 10% penalty tax you would have owed on your prior pre-age 59-1/2 distributions, plus interest on the penalty. Yow!! That hurts!

Exceptions to recapture tax. There are three exceptions to this recapture tax.

• No penalty tax recapture if the modification occurs after the later of age 59-1/2 or five years after you began the series of distributions; then you are free from the strictures of having to follow the method you began with.

• No penalty tax recapture will apply if distributions are modified on account of death or disability. (But those are rather unpleasant ways to avoid a tax.)

• I’ll talk about the third exception tomorrow, as it relates to the method you use for calculating these distributions.

I gotta go water my plants…..

Today’s post provides an overview of the exception; tomorrow I will go into how you actually calculate distributions that qualify. So here goes the overview.

You may take distributions from a tax-favored retirement plan at any time, without incurring the 10% penalty tax, if the distributions are structured as a series of distributions and the series consists of substantially equal periodic payments. These are rather strict requirements. And you will find that this technique for avoiding a penalty tax will not result in a large immediate distribution, so it will not be suitable if you’re looking to gain immediate access to a large chunk of your IRA. Rather, it can work well—if somewhat inflexibly—if you’re under 59-1/2 and you’re looking to spread your distributions over your lifetime.

Triggering event. If the distributions come from a traditional or Roth Individual Retirement Account, they do not have to be triggered by any particular event. You may start them at any time and any age. However, if they come out of an employer plan, to qualify they must begin after you have separated from service with the employer. Since most employer plans do not offer participants the option to take distributions in flexible ways, you are unlikely to be applying this exception to employer plan distributions. More likely, if you utilize this distribution method, it will be from an IRA.

Frequency of distributions. To qualify, the series of distributions must be periodic, no less frequently than annually. A series of monthly or quarterly distributions may also qualify.

Term of distributions. To qualify, the series must be calculated to occur over one of the following terms:

• Your life expectancy (more on this tomorrow)

• The joint life expectancy of you and your beneficiary

• Your actual lifetime (i.e., in the form of a life annuity)

• The actual lifetime of you and your beneficiary (i.e., in the form of a joint and survivor annuity).

Separate IRAs. In private letter rulings, the IRS has been liberal in allowing someone with two IRAs to calculate substantially equal periodic payments separately for one of the IRAs, while leaving the other IRA untouched; or alternatively, aggregating the IRAs for purposes of calculating the distributions.

Modification of periodic payments. Now, here’s the bad news. Once you start taking substantially equal periodic payments from an IRA, you should continue doing so at least until age 59-1/2, or, if later, five years from the initial distribution. If you modify your series of distributions before age 59-1/2 or five years—including ceasing your distributions—the IRS will recapture the 10% penalty tax you would have owed on your prior pre-age 59-1/2 distributions, plus interest on the penalty. Yow!! That hurts!

Exceptions to recapture tax. There are three exceptions to this recapture tax.

• No penalty tax recapture if the modification occurs after the later of age 59-1/2 or five years after you began the series of distributions; then you are free from the strictures of having to follow the method you began with.

• No penalty tax recapture will apply if distributions are modified on account of death or disability. (But those are rather unpleasant ways to avoid a tax.)

• I’ll talk about the third exception tomorrow, as it relates to the method you use for calculating these distributions.

I gotta go water my plants…..

Labels:

Savings Buckets

Thursday, February 19, 2009

Exceptions to the 10% Penalty

They say you can never be too rich, too thin, or too young. Well, the Tax Code thinks there is such a thing as too young. Distributions from tax-favored retirement plans before age 59-1/2 are hit with an extra 10% penalty tax in addition to whatever regular income tax you will have to pay. Ouch. (That, of course, assumes you can get a distribution—see yesterday’s post).

When you’re young, there are lots of good reasons to delay distributions. But if you want or need to get at some of your tax-favored dollars, there are many exceptions to the 10% penalty. There are so many exceptions, it’s become the Swiss cheese of tax penalties. Here is a summary.

• Dotage. No penalty if you have already reached age 59-1/2.

• Death. No penalty on distributions to your beneficiary after your death, even if the beneficiary is under age 59-1/2 and even if you were under 59-1/2 when you died.

• Disability. No penalty on distributions made after you are disabled.

• Defer. No penalty on a distribution that is moved to another tax-favored retirement plan in a tax-free rollover.

• Double-tax. No penalty on the portion of the distribution that is not subject to income tax, e.g., because it represents a return of your own after-tax contributions, as described in February 15’s post. (There’s a special rule for Roth IRAs, but that’s a subject for another post.)

• Done. No penalty if you terminate employment with your employer after reaching age 55, and distributions from the employer’s plan begin after your termination of employment. This exception does not apply to a traditional IRA or a Roth IRA.

• Doled. No penalty if the distribution is part of a series of substantially equal periodic payments from the tax-favored retirement plan. This exception allows you to begin distributions at any age, facilitating early retirement if that is your goal, and facilitating emergency access to some of your retirement funds. This is a big one. It’s the only exception that is within your control. And it will be the subject of a future post.

• Divorce. No penalty on distributions to an Alternate Payee (e.g., your former spouse or a minor child) under a Qualified Domestic Relations Order. This exception applies to employer plans, but not to IRAs. If you don’t know what Alternate Payee and Qualified Domestic Relations Order mean, consider yourself lucky. It’s all about marital strife.

• Dorms. No penalty on traditional or Roth Individual Retirement Account distributions (but not employer plan distributions) up to the amount of your higher education expenses for you, your spouse, your children and your grandchildren.

• Domicile. No penalty on distributions of up to $10,000 from a traditional or Roth IRA (but not from an employer plan) used to pay for a first home for you, your spouse, your child or your grandchild.

• Disease. No penalty on distributions up to the amount of your and your dependents’ deductible medical expenses (i.e., to the extent they exceed 7.5% of your Adjusted Gross Income). Better not to qualify for this one.

• Dismissed. No penalty on distributions from traditional or Roth IRAs (but not from employer plans) up to the amount of your health insurance premiums after you have been unemployed for at least 12 weeks.

• Dividends. No penalty on dividends on employer stock paid out to Employee Stock Ownership Plan participants.

• Distributed shares. The Net Unrealized Appreciation (NUA) on employer securities distributed from an employer plan may be temporarily excluded from income tax at the time of distribution if certain requirements are met. If you qualify for that exclusion, then the NUA is also not subject to the 10% penalty tax. The whole NUA thing is a worthy subject for a future post.

• Deferrals. No penalty if your employer’s 401(k) plan distributes back some of your elective deferral in order to meet certain tests.

• Death wish. Some employer plans (but not IRAs) purchase life insurance for the benefit of its participants, and the value of that insurance protection is currently taxed to the participant. Nonetheless, the value of that insurance protection is not subject to the 10% penalty tax.

• Duty. No penalty if you are a reservist called to active duty in the armed forces.

• Distant past. If you terminated employment before March 1, 1986, then distributions from your employer’s plan (but not from traditional or Roth IRAs) that are being made in accordance with an election signed before March 1, 1986, are not subject to the 10% penalty.

• Debt. No penalty on distributions to the IRS to satisfy a federal tax lien. Big whoop.

When you’re young, there are lots of good reasons to delay distributions. But if you want or need to get at some of your tax-favored dollars, there are many exceptions to the 10% penalty. There are so many exceptions, it’s become the Swiss cheese of tax penalties. Here is a summary.

• Dotage. No penalty if you have already reached age 59-1/2.

• Death. No penalty on distributions to your beneficiary after your death, even if the beneficiary is under age 59-1/2 and even if you were under 59-1/2 when you died.

• Disability. No penalty on distributions made after you are disabled.

• Defer. No penalty on a distribution that is moved to another tax-favored retirement plan in a tax-free rollover.

• Double-tax. No penalty on the portion of the distribution that is not subject to income tax, e.g., because it represents a return of your own after-tax contributions, as described in February 15’s post. (There’s a special rule for Roth IRAs, but that’s a subject for another post.)

• Done. No penalty if you terminate employment with your employer after reaching age 55, and distributions from the employer’s plan begin after your termination of employment. This exception does not apply to a traditional IRA or a Roth IRA.

• Doled. No penalty if the distribution is part of a series of substantially equal periodic payments from the tax-favored retirement plan. This exception allows you to begin distributions at any age, facilitating early retirement if that is your goal, and facilitating emergency access to some of your retirement funds. This is a big one. It’s the only exception that is within your control. And it will be the subject of a future post.

• Divorce. No penalty on distributions to an Alternate Payee (e.g., your former spouse or a minor child) under a Qualified Domestic Relations Order. This exception applies to employer plans, but not to IRAs. If you don’t know what Alternate Payee and Qualified Domestic Relations Order mean, consider yourself lucky. It’s all about marital strife.

• Dorms. No penalty on traditional or Roth Individual Retirement Account distributions (but not employer plan distributions) up to the amount of your higher education expenses for you, your spouse, your children and your grandchildren.

• Domicile. No penalty on distributions of up to $10,000 from a traditional or Roth IRA (but not from an employer plan) used to pay for a first home for you, your spouse, your child or your grandchild.

• Disease. No penalty on distributions up to the amount of your and your dependents’ deductible medical expenses (i.e., to the extent they exceed 7.5% of your Adjusted Gross Income). Better not to qualify for this one.

• Dismissed. No penalty on distributions from traditional or Roth IRAs (but not from employer plans) up to the amount of your health insurance premiums after you have been unemployed for at least 12 weeks.

• Dividends. No penalty on dividends on employer stock paid out to Employee Stock Ownership Plan participants.

• Distributed shares. The Net Unrealized Appreciation (NUA) on employer securities distributed from an employer plan may be temporarily excluded from income tax at the time of distribution if certain requirements are met. If you qualify for that exclusion, then the NUA is also not subject to the 10% penalty tax. The whole NUA thing is a worthy subject for a future post.

• Deferrals. No penalty if your employer’s 401(k) plan distributes back some of your elective deferral in order to meet certain tests.

• Death wish. Some employer plans (but not IRAs) purchase life insurance for the benefit of its participants, and the value of that insurance protection is currently taxed to the participant. Nonetheless, the value of that insurance protection is not subject to the 10% penalty tax.

• Duty. No penalty if you are a reservist called to active duty in the armed forces.

• Distant past. If you terminated employment before March 1, 1986, then distributions from your employer’s plan (but not from traditional or Roth IRAs) that are being made in accordance with an election signed before March 1, 1986, are not subject to the 10% penalty.

• Debt. No penalty on distributions to the IRS to satisfy a federal tax lien. Big whoop.

Labels:

Savings Buckets

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

Restricted Access to Retirement Funds

In a number of prior posts, I’ve extolled the long-term benefits of tax-favored savings buckets—IRA’s, Roth IRA’s, 401(k) plans, 403(b) plans and the like. But you have to take the bad with the good. Today I will talk about restrictions on access to your funds, which you should consider in weighing the pros against the cons.

At the outset, let me emphasize that I’m only talking about employer plans, such as 401(k) plans. The financial institution holding your IRA or Roth IRA will not prevent you from accessing those accounts. There may be a tax penalty imposed (and that’s a subject for a later post), or even an early withdrawal penalty (for example, in a certificate of deposit), but you can at least get at your assets if you need to. With employer plans, however, you can only get at your account at certain times. Here’s a summary.

Plan Document. Your employer’s plan document controls. It says when you can and can’t get at your account. What, you ask, is a plan document? That’s the 60-page, fine-print, legalese opus that nobody has ever actually read. But the plan’s distribution provisions are supposed to be summarized in a shorter, more readable “Summary Plan Description.” That’s the 20-page document which you got when you were first hired 20 years ago, put in a drawer for 10 years, and then threw out.

401(k) Restrictions. By law, 401(k) plans are not allowed to provide for a distribution to you unless you have reached some triggering event. The common allowable triggering events are (i) termination of your employment, (ii) financial hardship, and (iii) reaching age 59-1/2. But it’s important to understand that while these are permissible triggering events, your employer is not required to include them in its plan. So don’t go pounding your fist and insisting you’ve incurred a financial hardship if your employer’s plan doesn’t include that as a triggering event.

Latest Commencement Date. It is very common for 401(k) plans to provide for a distribution at your option shortly after you terminate employment. Very common, but not mandatory. The plan could require you to wait to get your distribution, as late as age 65. That kind of restriction is more common in pension plans, but it could be included in a 401(k) plan. In my entire career, I have never encountered that kind of restriction in a 401(k) plan, although it’s theoretically possible.

No Employer Discretion. Employer plans must not allow your company to exercise discretion in distributing or withholding benefit payments. So your employer can’t—legally anyway—delay distribution (if the plan provides for it) just because he doesn’t like you; nor can he accelerate distribution just because he does.

Method of Distribution. Your employer’s plan document governs not only when you can gain access to your account, but also how your account might be distributed. It’s typical—but not required—for a 401(k) plan to offer a lump sum. The plan might also offer an annuity, or a joint and survivor annuity for the lives of you and your spouse, or even installments over a stated period of years.

Spouse’s Rights. Federal law gives your spouse certain rights in your 401(k) account. Most notably, you must name your spouse as beneficiary in the event of your death before you’ve depleted the account. Also, if you opt for an annuity from a 401(k) plan, it must be in the form of a joint and survivor annuity with your spouse. Your spouse may waive these rights if certain formalities are met.

No Elimination of Distribution Options. Once a plan has given you a distribution option, your employer generally can’t take it away by amending the plan, at least with respect to your existing account balance. There are, however, a bunch of exceptions to this general rule.

Mandatory Distributions. On the other side of the coin, neither you nor the plan may defer distributions forever. There’s a set of rules, called the Required Minimum Distribution rules, which generally requires that you begin distributions no later than age 70-1/2 (or, in the case of an employer plan, retirement if later); and you must deplete the account at a certain minimum prescribed rate. I think I’ll provide more details on Required Minimum Distributions in a future post.

Loans. Some 401(k) plans allow you to borrow from your account. That’s not really a distribution because you have to pay it back. But it’s a limited form of access that may prove useful in a pinch. Plan loans are not a great idea, and that’s something I’ll discuss in a later post.

So these are the restrictions you’ll need to weigh against the tax benefits of shifting your savings into a tax-favored plan. In tomorrow’s post, I’ll talk about a different tax detriment—the 10% penalty tax on distributions before age 59-1/2.

At the outset, let me emphasize that I’m only talking about employer plans, such as 401(k) plans. The financial institution holding your IRA or Roth IRA will not prevent you from accessing those accounts. There may be a tax penalty imposed (and that’s a subject for a later post), or even an early withdrawal penalty (for example, in a certificate of deposit), but you can at least get at your assets if you need to. With employer plans, however, you can only get at your account at certain times. Here’s a summary.

Plan Document. Your employer’s plan document controls. It says when you can and can’t get at your account. What, you ask, is a plan document? That’s the 60-page, fine-print, legalese opus that nobody has ever actually read. But the plan’s distribution provisions are supposed to be summarized in a shorter, more readable “Summary Plan Description.” That’s the 20-page document which you got when you were first hired 20 years ago, put in a drawer for 10 years, and then threw out.

401(k) Restrictions. By law, 401(k) plans are not allowed to provide for a distribution to you unless you have reached some triggering event. The common allowable triggering events are (i) termination of your employment, (ii) financial hardship, and (iii) reaching age 59-1/2. But it’s important to understand that while these are permissible triggering events, your employer is not required to include them in its plan. So don’t go pounding your fist and insisting you’ve incurred a financial hardship if your employer’s plan doesn’t include that as a triggering event.

Latest Commencement Date. It is very common for 401(k) plans to provide for a distribution at your option shortly after you terminate employment. Very common, but not mandatory. The plan could require you to wait to get your distribution, as late as age 65. That kind of restriction is more common in pension plans, but it could be included in a 401(k) plan. In my entire career, I have never encountered that kind of restriction in a 401(k) plan, although it’s theoretically possible.

No Employer Discretion. Employer plans must not allow your company to exercise discretion in distributing or withholding benefit payments. So your employer can’t—legally anyway—delay distribution (if the plan provides for it) just because he doesn’t like you; nor can he accelerate distribution just because he does.

Method of Distribution. Your employer’s plan document governs not only when you can gain access to your account, but also how your account might be distributed. It’s typical—but not required—for a 401(k) plan to offer a lump sum. The plan might also offer an annuity, or a joint and survivor annuity for the lives of you and your spouse, or even installments over a stated period of years.

Spouse’s Rights. Federal law gives your spouse certain rights in your 401(k) account. Most notably, you must name your spouse as beneficiary in the event of your death before you’ve depleted the account. Also, if you opt for an annuity from a 401(k) plan, it must be in the form of a joint and survivor annuity with your spouse. Your spouse may waive these rights if certain formalities are met.

No Elimination of Distribution Options. Once a plan has given you a distribution option, your employer generally can’t take it away by amending the plan, at least with respect to your existing account balance. There are, however, a bunch of exceptions to this general rule.

Mandatory Distributions. On the other side of the coin, neither you nor the plan may defer distributions forever. There’s a set of rules, called the Required Minimum Distribution rules, which generally requires that you begin distributions no later than age 70-1/2 (or, in the case of an employer plan, retirement if later); and you must deplete the account at a certain minimum prescribed rate. I think I’ll provide more details on Required Minimum Distributions in a future post.

Loans. Some 401(k) plans allow you to borrow from your account. That’s not really a distribution because you have to pay it back. But it’s a limited form of access that may prove useful in a pinch. Plan loans are not a great idea, and that’s something I’ll discuss in a later post.

So these are the restrictions you’ll need to weigh against the tax benefits of shifting your savings into a tax-favored plan. In tomorrow’s post, I’ll talk about a different tax detriment—the 10% penalty tax on distributions before age 59-1/2.

Labels:

Savings Buckets

Tuesday, February 17, 2009

My, How the Little Things Add Up

In a number of prior posts I’ve discussed some ideas for making your retirement savings go further. For the most part, each idea is a modestly good idea, but taken together, they can add up to a great idea. Huge! And that’s today’s task—to put it all together with an example. The results are amazing and heartening.

Consider Wally Cleaver. He’s grown up now. In fact, he’s age 40, with a family and everything. To date, Wally has saved $50,000 in a taxable investment account. Wally has analyzed his many savings options. He thinks of them as creating many different futures—Wally Worlds, if you will. Wally projects how much each additional good idea, layered on top of the others, will add to his annual after-tax retirement spending. All of his projections are shown in real, inflation-adjusted dollars, to keep them meaningful. And all in after-tax dollars, as well, because you can't spend money that goes to the government. The assumptions that went into Wally’s projections are shown in the chart below.

Wally World One. $6,320 per year.

Wally does nothing special and continues to invest his existing savings in an ordinary taxable investment account. He projects that his $50,000 of savings will eventually, at age 65, buy him a retirement of $6,320 per year. A nice start.

Wally World Two. $7,268 per year.

Wally decides to do the hard thing—to forego some spending this year and add $7,500 to his investment account. (In fact, he postpones a planned cross-country trip with his wife and kids to a Disney-esque amusement park.) Giving up some luxuries hurts, but it adds $948 to his annual retirement spending. That’s after-tax and expressed in today’s dollars. Foregoing the pleasures of consumption is the hard part. It gets easier from here.

Wally World Three. $7,950 per year.

Instead of adding $7,500 to his taxable investment account, Wally makes a $10,000 pre-tax elective deferral to his employer’s 401(k) plan. It costs him the same $7,500 as in Wally World Two because he is in the 25% tax bracket. Just by contributing his savings to the right bucket, Wally has increased his future after-tax retirement spending by another $652 per year. Way to go, Wally!

Wally World Four. $8,398 per year.

Wally increases his 401(k) deferral to the maximum $16,500. But he doesn’t decrease his spending by more than the $7,500 of Wally World Two. Rather, as described in February 8’s post, he spends $4,875 from his taxable savings account (shrinking it to $45,125). Because of the tax deduction, it only costs him $4,875 to increase his 401(k) deferral by $6,500. And doing this adds $448 to his retirement spending. Here’s something worth noting: The last two steps combined added more to Wally’s projected retirement spending than did his painful and heroic effort to save $7,500. And they didn’t require any further spending reductions! Oh, happy day! But wait; there’s more!

Wally World Five. $8,722 per year.

Wally has read January 15’s post and decides to make the $16,500 deferral on a Roth basis. The loss of a deduction costs him $4,125 of additional taxes (further reducing his investment account to $41,000). But it has a long-run tax benefit, which increases his projected after-tax retirement spending by an additional $324. Hey. Why not?

Wally World Six. $8,919 per year.

After reading February 15’s post, Wally decides to take another $5,000 out of his investment account (reducing it to $36,000), and use it to open a $5,000 IRA. He has read February 14’s post and has concluded that the contribution won’t be deductible to him, but he finds it to be a worthwhile step nonetheless. In fact, he projects it will add another $197 to his annual retirement spending. And, again, without breaking a sweat.

Wally World Seven. $9,217 per year.

Wally decides to expend some effort to lower his investment costs for his (now three) savings buckets, as described in yesterday’s post. He finds he is able to shave his expenses by a modest 0.1% (10 basis points, in investment world jargon). Wally projects that this modest savings will increase his after-tax retirement spending by another $298 per year. Not a huge amount, but he’ll take it.

Wally World Eight. $9,630 per year.

Wally has read February 12’s post, and decides to do some future spigot planning. When he gets to retirement, instead of spending down his three savings buckets proportionately (as was assumed in prior Worlds), he plans to spend them down in the order that will optimize his annual after-tax spending. He projects that doing this will increase his after-tax spending by another $413. It’s money for nothin’!

Wally World Nine. $10,636 per year.

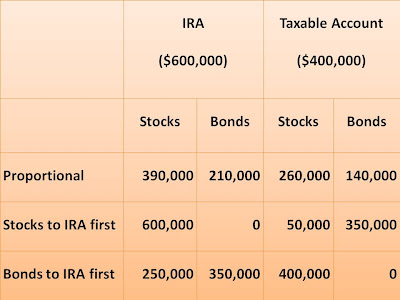

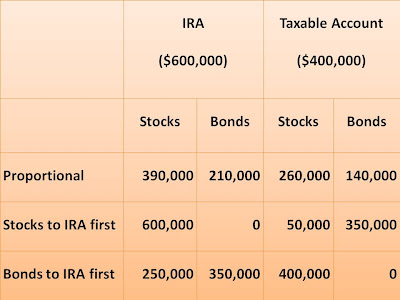

Wally decides to go further and engage in asset location planning (after reading February 13’s post). He projects that by cleverly allocating his stocks and bonds among his three savings buckets he can increase his retirement spending by another $1,006 per year compared to investing his three savings buckets in the same stock/bond proportion. Cool!

Wally World Ten. $10,967 per year.

What! Yet another world? Yes. Wally has read February 10’s post, and, seeing that he has adjusted gross income of less than $100,000, he realizes he can convert his new $5,000 traditional IRA to a Roth IRA. (And in Wally’s unusual situation, he pays no income tax to do so. The value of his IRA is equal to his after-tax contributions, and he only has to pay income tax on the difference, which is zero.) He projects that this step will increase his retirement spending by another $331. Free money!

Now just look at the aggregate results. Struggling to save $7,500 added $948 per year to Wally’s future retirement security. But just being clever about how he arranges his savings, adds even more: another $3,698. That’s a four-fold increase! Who knew?!

Consider Wally Cleaver. He’s grown up now. In fact, he’s age 40, with a family and everything. To date, Wally has saved $50,000 in a taxable investment account. Wally has analyzed his many savings options. He thinks of them as creating many different futures—Wally Worlds, if you will. Wally projects how much each additional good idea, layered on top of the others, will add to his annual after-tax retirement spending. All of his projections are shown in real, inflation-adjusted dollars, to keep them meaningful. And all in after-tax dollars, as well, because you can't spend money that goes to the government. The assumptions that went into Wally’s projections are shown in the chart below.

Wally World One. $6,320 per year.

Wally does nothing special and continues to invest his existing savings in an ordinary taxable investment account. He projects that his $50,000 of savings will eventually, at age 65, buy him a retirement of $6,320 per year. A nice start.

Wally World Two. $7,268 per year.

Wally decides to do the hard thing—to forego some spending this year and add $7,500 to his investment account. (In fact, he postpones a planned cross-country trip with his wife and kids to a Disney-esque amusement park.) Giving up some luxuries hurts, but it adds $948 to his annual retirement spending. That’s after-tax and expressed in today’s dollars. Foregoing the pleasures of consumption is the hard part. It gets easier from here.

Wally World Three. $7,950 per year.

Instead of adding $7,500 to his taxable investment account, Wally makes a $10,000 pre-tax elective deferral to his employer’s 401(k) plan. It costs him the same $7,500 as in Wally World Two because he is in the 25% tax bracket. Just by contributing his savings to the right bucket, Wally has increased his future after-tax retirement spending by another $652 per year. Way to go, Wally!

Wally World Four. $8,398 per year.

Wally increases his 401(k) deferral to the maximum $16,500. But he doesn’t decrease his spending by more than the $7,500 of Wally World Two. Rather, as described in February 8’s post, he spends $4,875 from his taxable savings account (shrinking it to $45,125). Because of the tax deduction, it only costs him $4,875 to increase his 401(k) deferral by $6,500. And doing this adds $448 to his retirement spending. Here’s something worth noting: The last two steps combined added more to Wally’s projected retirement spending than did his painful and heroic effort to save $7,500. And they didn’t require any further spending reductions! Oh, happy day! But wait; there’s more!

Wally World Five. $8,722 per year.

Wally has read January 15’s post and decides to make the $16,500 deferral on a Roth basis. The loss of a deduction costs him $4,125 of additional taxes (further reducing his investment account to $41,000). But it has a long-run tax benefit, which increases his projected after-tax retirement spending by an additional $324. Hey. Why not?

Wally World Six. $8,919 per year.

After reading February 15’s post, Wally decides to take another $5,000 out of his investment account (reducing it to $36,000), and use it to open a $5,000 IRA. He has read February 14’s post and has concluded that the contribution won’t be deductible to him, but he finds it to be a worthwhile step nonetheless. In fact, he projects it will add another $197 to his annual retirement spending. And, again, without breaking a sweat.

Wally World Seven. $9,217 per year.

Wally decides to expend some effort to lower his investment costs for his (now three) savings buckets, as described in yesterday’s post. He finds he is able to shave his expenses by a modest 0.1% (10 basis points, in investment world jargon). Wally projects that this modest savings will increase his after-tax retirement spending by another $298 per year. Not a huge amount, but he’ll take it.

Wally World Eight. $9,630 per year.

Wally has read February 12’s post, and decides to do some future spigot planning. When he gets to retirement, instead of spending down his three savings buckets proportionately (as was assumed in prior Worlds), he plans to spend them down in the order that will optimize his annual after-tax spending. He projects that doing this will increase his after-tax spending by another $413. It’s money for nothin’!

Wally World Nine. $10,636 per year.

Wally decides to go further and engage in asset location planning (after reading February 13’s post). He projects that by cleverly allocating his stocks and bonds among his three savings buckets he can increase his retirement spending by another $1,006 per year compared to investing his three savings buckets in the same stock/bond proportion. Cool!

Wally World Ten. $10,967 per year.

What! Yet another world? Yes. Wally has read February 10’s post, and, seeing that he has adjusted gross income of less than $100,000, he realizes he can convert his new $5,000 traditional IRA to a Roth IRA. (And in Wally’s unusual situation, he pays no income tax to do so. The value of his IRA is equal to his after-tax contributions, and he only has to pay income tax on the difference, which is zero.) He projects that this step will increase his retirement spending by another $331. Free money!

Now just look at the aggregate results. Struggling to save $7,500 added $948 per year to Wally’s future retirement security. But just being clever about how he arranges his savings, adds even more: another $3,698. That’s a four-fold increase! Who knew?!

Labels:

Retirement Planning,

Savings Buckets

Monday, February 16, 2009

Investment Expenses

A little bit of cost control can pay off big time in the long run.

There are lots of administrative costs to investing, and if you can find ways to shave them just a little bit—without sacrificing the quality of advice that often comes with them—you can painlessly improve your future retirement security.

Here’s a quick example. Patty starts saving $10,000 per year at age 40 in some kind of tax-favored retirement plan. The annual administrative expense built into the plan is 0.4% of her assets. Using some reasonable assumptions, Patty figures as a result of her saving, she can expect retirement spending of $28,325 per year, beginning at age 65. Her cousin Cathy is identical to Patty, same age, savings, etc. Except that Cathy has lived most everywhere, and is a bit smarter than Patty. (In fact, she’s a bit of a Little Miss Smarty Pants.) Anyway, she manages to cut her administrative expenses by one-tenth of a percentage point (aka, 10 basis points, in financial world jargon) to 0.3%. Cathy projects annual spending of $29,067, which represents a 2.6% increase over Patty’s.

Admittedly, a 2.6% increase is not huge. Enhancing your retirement spending by a small amount like that is not a great idea. But it’s a modestly good idea. And when melded with all the other modestly good ideas available to you, it adds up. Anyway, it’s better than a headache.

What kind of administrative expenses are you incurring that might be eroding your savings? There’s lots of them: investment advisor fees, asset custodian fees, account maintenance fees, brokerage commissions, accounting expenses. If your account is inside an employer retirement plan, there are other fees as well: trustee fees, recordkeeping fees, accounting fees, legal fees. The list goes on. Some of these fees may be picked up by your employer, and others may be charged to your account.

Some of these fees may be disclosed, and some hidden. Often all you will ever see on your statement is the net return (or loss, of late) for the quarter, with no explicit statement of what size fee got you down to that net. Some services may be bundled, making it difficult to break out how much you’re paying for what service.

Sometimes there are fees layered upon fees. For example, your 401(k) plan may be invested in mutual funds. There may be some fees charged by the plan, and other fees charged by the mutual fund.

The more you can learn about the fees that erode your account, the better able you will be to find ways to shave them, to intelligently assess which fees are appropriate for the value added, and which can be shrunk without damage to your overall wellbeing.

That’s the theory anyway.

There are lots of administrative costs to investing, and if you can find ways to shave them just a little bit—without sacrificing the quality of advice that often comes with them—you can painlessly improve your future retirement security.