Yesterday’s post discussed the costs of turnover in your account—the selling and buying of stocks. I thought it would be instructive to quantify the tax costs of turnover to see just how much it’s worth worrying about. It turns out that over time, the tax cost can be meaningful. Remember, this discussion only applies to taxable investment accounts, since turnover inside tax-favored retirement accounts is tax-neutral; it carries no tax cost.

Let me describe two little experiments. The first applies to those who are not yet retired and are still accumulating assets and the second applies to those who are in retirement and spending down their assets.

The first experiment. Picture a hypothetical person just like you (but not as good looking). At age 30, he’s got $1,000,000 of cash to invest, which he intends to invest 75% in stocks and 25% in bonds. His goal is to accumulate a retirement fund at age 65. Assume all gains are long-term capital gains, and there are no commission costs. Applying reasonable assumptions, with very modest turnover (1% per year, which is about right for an index fund), he can expect to accumulate $4,512,913 in real (inflation-adjusted) dollars, after taxes.

Now change just the turnover assumption to 70% annual turnover (not unusual for an actively managed stock fund). Capital gains tax costs lower the after-tax accumulation at age 65 to $3,677,357. That’s a 19% drop in the retirement fund, which would likely translate into a 19% drop in available retirement spending. Small costs add up!

Now the second experiment. Picture someone age 65, with a $5,000,000 taxable account. She plans to spend an amount which will leave her children with half her wealth remaining if she were to die 30 years hence at age 95. She plans to invest her account 50% in stocks and 50% in bonds. Assume only a modest 1% turnover, and her after-tax allowance from this taxable account is $208,050. Change that turnover assumption to 70%, and her after-tax allowance drops to $190,225. That’s a 9% cut in lifestyle.

Again, turnover matters.

Thursday, April 30, 2009

Wednesday, April 29, 2009

Turnover

Turnover carries costs. I’m not talking about those flaky fruit-filled pastries that Pillsbury sells. I’m talking about the selling and buying of stocks in your investment account.

First, there are the obvious transaction costs. When you sell one stock and buy another, you incur a commission cost. Commission costs have gone down in recent years, but they’re still not zero. Then there’s the spread between the stock’s bid and ask prices, the difference between what buyers are offering to pay and what sellers are willing to sell for. That’s another cost.

There’s also a tax cost if your securities are in a taxable investment account: the capital gains tax you incur if the stock has appreciated. (This tax discussion does not apply to sales inside tax-favored retirement accounts like traditional IRA’s and Roth IRA’s. Which is why those types of accounts can make you a better investor, as described in April 20’s post.) For as long as you hold a stock, its appreciation is tax-free to you. You get to determine when to pay the tax on that appreciation by choosing when to sell the stock. You can defer tax by deferring the sale. In fact, under current law, if you delay long enough and die holding an appreciated stock, your heirs get a new tax basis equal to the stock’s value at the date of your death, so nobody ever pays tax on the appreciation. What a deal! Makes you feel kind of foolish, doesn’t it, for having sold that Google stock the week before you got hit by a bus. (The rule about disappearing gains at death is scheduled to change next year, but there’s reason to believe Congress might act to keep the old rule. Watch this space for developments.)

Under the circumstances, why have any turnover? Well, there are plenty of good reasons for turnover. First, you may own a stock that did well for a while, but which you think is no longer a good investment. Second, you may need to sell an appreciated stock to generate cash to meet your spending needs. You can’t eat appreciation. Third, you may need to sell an appreciated stock to rebalance your portfolio back to your desired asset allocation mix.

But just because you have to have some turnover does not mean it has to be excessive. You can be astute about how you manage your stock sales. You can wait until short-term gain has ripened into long-term gain (generally, after one year and a day), since long-term gains enjoy significantly lower tax rates. You can offset gains by also selling some depreciated stocks. You can arrange your stock sales to serve triple duty: investment changes, cash generation, and asset class rebalancing, all at the same time.

One easy way to reduce excessive turnover is to invest in index funds rather than actively managed funds. By their nature, index funds tend to have low turnover, since not too many stocks enter or leave the index. Conversely, actively managed funds tend to have higher turnover, as fund managers make frequent sell and buy decisions. An in-between approach is to select a tax-efficient stock fund, where the fund managers take tax costs into account as they make their sell and buy decisions.

Okay. So there’s a tax cost to turnover. Just how significant is that cost? More on that tomorrow.

First, there are the obvious transaction costs. When you sell one stock and buy another, you incur a commission cost. Commission costs have gone down in recent years, but they’re still not zero. Then there’s the spread between the stock’s bid and ask prices, the difference between what buyers are offering to pay and what sellers are willing to sell for. That’s another cost.

There’s also a tax cost if your securities are in a taxable investment account: the capital gains tax you incur if the stock has appreciated. (This tax discussion does not apply to sales inside tax-favored retirement accounts like traditional IRA’s and Roth IRA’s. Which is why those types of accounts can make you a better investor, as described in April 20’s post.) For as long as you hold a stock, its appreciation is tax-free to you. You get to determine when to pay the tax on that appreciation by choosing when to sell the stock. You can defer tax by deferring the sale. In fact, under current law, if you delay long enough and die holding an appreciated stock, your heirs get a new tax basis equal to the stock’s value at the date of your death, so nobody ever pays tax on the appreciation. What a deal! Makes you feel kind of foolish, doesn’t it, for having sold that Google stock the week before you got hit by a bus. (The rule about disappearing gains at death is scheduled to change next year, but there’s reason to believe Congress might act to keep the old rule. Watch this space for developments.)

Under the circumstances, why have any turnover? Well, there are plenty of good reasons for turnover. First, you may own a stock that did well for a while, but which you think is no longer a good investment. Second, you may need to sell an appreciated stock to generate cash to meet your spending needs. You can’t eat appreciation. Third, you may need to sell an appreciated stock to rebalance your portfolio back to your desired asset allocation mix.

But just because you have to have some turnover does not mean it has to be excessive. You can be astute about how you manage your stock sales. You can wait until short-term gain has ripened into long-term gain (generally, after one year and a day), since long-term gains enjoy significantly lower tax rates. You can offset gains by also selling some depreciated stocks. You can arrange your stock sales to serve triple duty: investment changes, cash generation, and asset class rebalancing, all at the same time.

One easy way to reduce excessive turnover is to invest in index funds rather than actively managed funds. By their nature, index funds tend to have low turnover, since not too many stocks enter or leave the index. Conversely, actively managed funds tend to have higher turnover, as fund managers make frequent sell and buy decisions. An in-between approach is to select a tax-efficient stock fund, where the fund managers take tax costs into account as they make their sell and buy decisions.

Okay. So there’s a tax cost to turnover. Just how significant is that cost? More on that tomorrow.

Labels:

Investments

Tuesday, April 28, 2009

Frequency of Losses—Asset Class Mixture

Sunday’s post looked at one aspect of risk—a very narrow aspect, at that—and compared the riskiness of stocks and bonds. But of course nobody ought to have all of their retirement investments solely in one asset class or another. How risky is investing if your assets are in a mixture of stocks and bonds?

I’m glad you asked. The green line in the graph below builds on the information shown in Sunday’s post. It answers the musical question, “In the past, how frequently would you have experienced a real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) loss if your assets were invested 50% in stocks and 50% in bonds?”

As in Sunday’s post, the answer depends on how frequently you choose to measure your investment progress. Historically, a 50%-50% mixture of stocks and bonds has been slightly less risky—at least as measured by this particular and narrow dimension of risk—than either stocks or bonds standing alone. If you had looked at your investments every calendar year, your mixture would have shown a real loss during 31% of the 83 years studied. That is slightly better than 33% for 100% stocks and 39% for 100% bonds.

And, as with stocks alone or bonds alone, the green line shows a generally decreasing frequency of real losses as you increase the length of time between measurements. With a 50%-50% mixture, in the past 83 years there has been no period of 18 years or longer during which such a mixture exhibited a real loss.

Important: Note that the green line is mostly lower than either the blue line (100% stocks) or the red line (100% bonds). Which means that a nice mixture of stocks and bonds has proven less risky than putting all your eggs in one basket. At least as measured by this particular (and limited) facet of risk.

But, like a Batman villain, risk has many faces. More to come.

I’m glad you asked. The green line in the graph below builds on the information shown in Sunday’s post. It answers the musical question, “In the past, how frequently would you have experienced a real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) loss if your assets were invested 50% in stocks and 50% in bonds?”

As in Sunday’s post, the answer depends on how frequently you choose to measure your investment progress. Historically, a 50%-50% mixture of stocks and bonds has been slightly less risky—at least as measured by this particular and narrow dimension of risk—than either stocks or bonds standing alone. If you had looked at your investments every calendar year, your mixture would have shown a real loss during 31% of the 83 years studied. That is slightly better than 33% for 100% stocks and 39% for 100% bonds.

And, as with stocks alone or bonds alone, the green line shows a generally decreasing frequency of real losses as you increase the length of time between measurements. With a 50%-50% mixture, in the past 83 years there has been no period of 18 years or longer during which such a mixture exhibited a real loss.

Important: Note that the green line is mostly lower than either the blue line (100% stocks) or the red line (100% bonds). Which means that a nice mixture of stocks and bonds has proven less risky than putting all your eggs in one basket. At least as measured by this particular (and limited) facet of risk.

But, like a Batman villain, risk has many faces. More to come.

Labels:

Investments

Monday, April 27, 2009

The 4% Plan vs. 3% Plan vs. 3.5% Plan

A number of prior posts have mentioned the 4% Plan. That’s one of a few schemes for rationally spending down your assets once you have retired and switched from saving to consuming. But whether 4% is the “right” number will depend on many factors. One of them is the type of savings buckets in which your assets dwell.

First, what is the 4% Plan? Under the 4% Plan, you add up your investment assets on the day after your retirement party, multiply by 4%, and that’s your budget for the year. Then every year you increase the dollar amount by the prior year’s inflation, and you've got yourself a new budget. I’m not crazy about the 4% Plan, but at least it’s a plan, and it's simple enough.

Of course, nothing’s simple. Because taxes matter, and one of the important variables we have glossed over is this: In which of the three main types of savings buckets do your assets sit? Are they in a pre-tax retirement account like a traditional Individual Retirement Account? Or a newfangled Roth account? Or a taxable investment account? (Chances are they are in some combination of the three, but for the sake of discussion, let’s pretend they are all in one or another.)

Here’s why the answer matters. The number 4% was arrived at by financial professionals to result in a distribution amount that is as big as possible, while still maintaining a high likelihood that you will not run out of assets during your lifetime (or the joint lifetimes of you and your spouse). The professionals who arrived at that figure assumed your assets were invested in a traditional tax-favored retirement account, like a 401(k) account or IRA.

So let’s follow that through. Let’s say on your retirement day you have $1,000,000 saved in a traditional IRA. You figure 4% is $40,000, so that (plus future inflation) is your budget. But what about taxes? You haven’t paid taxes yet! If, for example, your overall marginal income rate is 25%, then $10,000 goes to pay your taxes, and you are left to live on $30,000. You can’t eat taxes. 4%, it turns out, is the rate at which you can deplete the account; not necessarily what you get to spend. That looks more like 3%.

Now let’s change the facts. Say you have the same $1,000,000, but it’s not in a traditional IRA; instead it’s in a Roth IRA. Your sustainable distribution is the same 4%, or $40,000, but now all income taxes have already been paid, so you get to spend the whole $40,000 on yourself. With a Roth savings bucket, 4% is truly 4%.

One more scenario. Assume the $1,000,000 is in a taxable investment account. You’ve already paid income taxes on that $1,000,000 so you get to spend your entire distribution on yourself. But it should be a bit less than 4% in this case. I’m not sure how much less, but I think probably around 3.5%, or $35,000 in the example. Why do you have to shave the 4% down? Because the professionals who came up with the 4% number assumed you were investing your $1,000,000 in some sort of tax-exempt environment, like an IRA, in which you would not have to pay income tax on your investment earnings (although you would have to pay income tax on your distributions, as we saw two paragraphs above). So if your investment returns (not your distributions) have to be shaved by income taxes, it stands to reason that your long run sustainable distribution percentage will have to be shaved as well. Perhaps down to 3.5%. For a description of the factors that go into this particular haircut, see February 3’s post.

As I said, in reality your retirement savings will likely be housed in all three types of savings buckets, so your own spending percentage will be some blend of the three numbers.

Oh, by the way, your own percentage will also vary depending upon your asset allocation plan. But that discussion is for another day.

First, what is the 4% Plan? Under the 4% Plan, you add up your investment assets on the day after your retirement party, multiply by 4%, and that’s your budget for the year. Then every year you increase the dollar amount by the prior year’s inflation, and you've got yourself a new budget. I’m not crazy about the 4% Plan, but at least it’s a plan, and it's simple enough.

Of course, nothing’s simple. Because taxes matter, and one of the important variables we have glossed over is this: In which of the three main types of savings buckets do your assets sit? Are they in a pre-tax retirement account like a traditional Individual Retirement Account? Or a newfangled Roth account? Or a taxable investment account? (Chances are they are in some combination of the three, but for the sake of discussion, let’s pretend they are all in one or another.)

Here’s why the answer matters. The number 4% was arrived at by financial professionals to result in a distribution amount that is as big as possible, while still maintaining a high likelihood that you will not run out of assets during your lifetime (or the joint lifetimes of you and your spouse). The professionals who arrived at that figure assumed your assets were invested in a traditional tax-favored retirement account, like a 401(k) account or IRA.

So let’s follow that through. Let’s say on your retirement day you have $1,000,000 saved in a traditional IRA. You figure 4% is $40,000, so that (plus future inflation) is your budget. But what about taxes? You haven’t paid taxes yet! If, for example, your overall marginal income rate is 25%, then $10,000 goes to pay your taxes, and you are left to live on $30,000. You can’t eat taxes. 4%, it turns out, is the rate at which you can deplete the account; not necessarily what you get to spend. That looks more like 3%.

Now let’s change the facts. Say you have the same $1,000,000, but it’s not in a traditional IRA; instead it’s in a Roth IRA. Your sustainable distribution is the same 4%, or $40,000, but now all income taxes have already been paid, so you get to spend the whole $40,000 on yourself. With a Roth savings bucket, 4% is truly 4%.

One more scenario. Assume the $1,000,000 is in a taxable investment account. You’ve already paid income taxes on that $1,000,000 so you get to spend your entire distribution on yourself. But it should be a bit less than 4% in this case. I’m not sure how much less, but I think probably around 3.5%, or $35,000 in the example. Why do you have to shave the 4% down? Because the professionals who came up with the 4% number assumed you were investing your $1,000,000 in some sort of tax-exempt environment, like an IRA, in which you would not have to pay income tax on your investment earnings (although you would have to pay income tax on your distributions, as we saw two paragraphs above). So if your investment returns (not your distributions) have to be shaved by income taxes, it stands to reason that your long run sustainable distribution percentage will have to be shaved as well. Perhaps down to 3.5%. For a description of the factors that go into this particular haircut, see February 3’s post.

As I said, in reality your retirement savings will likely be housed in all three types of savings buckets, so your own spending percentage will be some blend of the three numbers.

Oh, by the way, your own percentage will also vary depending upon your asset allocation plan. But that discussion is for another day.

Labels:

Retirement Spending Plan

Sunday, April 26, 2009

Frequency of Investment Losses

There are many, many facets of investment risk and uncertainty. I catalogued a bunch of them in March 16’s post. Today’s post focuses on just one aspect of investment risk: How frequently can you expect to experience a loss?

First, let me narrow the inquiry. How frequently might you expect to experience a real, i.e., inflation-adjusted, loss? If you just look at the nominal value of your account, your perceived losses will be much less frequent. But we’re much too wise to ignore the hidden loss engendered by inflation. So we’ll ask the question “How frequently can you expect the inflation-adjusted value of your account to decline when you invest in different asset classes—stocks and bonds?”

Not surprisingly, the answer depends on how frequently you look at your account statement. The shorter the interval, the more frequent the incidence of real loss. Time erases all losses. Time also erases outsized gains, but that’s an inquiry for another day; today we look at losses.

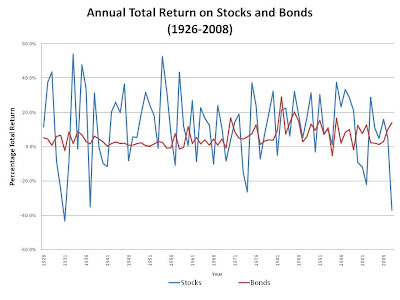

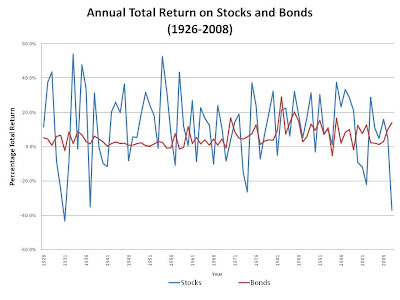

If you look at your investment results every calendar year you’ll find that a sickeningly high percentage of the time you will have realized an inflation-adjusted loss. 33% with stocks and 39% with bonds. Where did these percentages come from? I looked at the 83 years from 1926 through 2008 (yes, that horrible 2008). For stocks, I measured the total return on the S&P 500; for bonds, I measured the total return on intermediate term treasury bonds; for inflation, I measured the change in the Consumer Price Index.

But if you expand the interval between measurements—increasing the interval from one year to every two years, things improve a bit. The percentage of losing periods drops to 27% for stocks and 32% for bonds. And so the trend continues, as shown in the graph below. Although the trend is more pronounced for stocks than for bonds. By the time your time horizon increases to 18 years, you find that stocks have not shown a real loss for any period of 18 years or longer between 1926 and 2008. For bonds, the magic number is somewhat higher—the interval has to be 50 years before you can say bonds have never exhibited real losses during the 83 years studied.

So time heals all losses. But there’s four hairballs on this particular lollypop: (i) the future might be worse than the past; (ii) you might simply not have enough time to recoup your losses; (iii) the scariness of the ride along the way (think 2008) might cause you to change your asset allocation in ways you’ll later regret; and (iv) the graph says absolutely nothing about the magnitude of losses, just the frequency. Magnitude is for another day.

First, let me narrow the inquiry. How frequently might you expect to experience a real, i.e., inflation-adjusted, loss? If you just look at the nominal value of your account, your perceived losses will be much less frequent. But we’re much too wise to ignore the hidden loss engendered by inflation. So we’ll ask the question “How frequently can you expect the inflation-adjusted value of your account to decline when you invest in different asset classes—stocks and bonds?”

Not surprisingly, the answer depends on how frequently you look at your account statement. The shorter the interval, the more frequent the incidence of real loss. Time erases all losses. Time also erases outsized gains, but that’s an inquiry for another day; today we look at losses.

If you look at your investment results every calendar year you’ll find that a sickeningly high percentage of the time you will have realized an inflation-adjusted loss. 33% with stocks and 39% with bonds. Where did these percentages come from? I looked at the 83 years from 1926 through 2008 (yes, that horrible 2008). For stocks, I measured the total return on the S&P 500; for bonds, I measured the total return on intermediate term treasury bonds; for inflation, I measured the change in the Consumer Price Index.

But if you expand the interval between measurements—increasing the interval from one year to every two years, things improve a bit. The percentage of losing periods drops to 27% for stocks and 32% for bonds. And so the trend continues, as shown in the graph below. Although the trend is more pronounced for stocks than for bonds. By the time your time horizon increases to 18 years, you find that stocks have not shown a real loss for any period of 18 years or longer between 1926 and 2008. For bonds, the magic number is somewhat higher—the interval has to be 50 years before you can say bonds have never exhibited real losses during the 83 years studied.

So time heals all losses. But there’s four hairballs on this particular lollypop: (i) the future might be worse than the past; (ii) you might simply not have enough time to recoup your losses; (iii) the scariness of the ride along the way (think 2008) might cause you to change your asset allocation in ways you’ll later regret; and (iv) the graph says absolutely nothing about the magnitude of losses, just the frequency. Magnitude is for another day.

Labels:

Investments

Saturday, April 25, 2009

Refundable vs. Nonrefundable Saver’s Credit

Yesterday’s post described the Saver’s Credit, a taxpayer-paid matching contribution designed to encourage and assist low income workers to save for their retirement. In a thoughtful comment, David highlighted the purpose of the Saver's Credit, which is to asist low-income workers in saving for their own retirement.

Which leads me to focus on one particular feature of the Saver's Credit: it’s a nonrefundable credit. That’s tax jargon for a credit that is limited to your tax liability. A nonrefundable credit can only operate to reduce your tax liability. If your potential credit is a dollar more than your tax liability, you don’t get that extra dollar.

There’s currently a bill recently introduced into the House of Representatives by Congressman Pomeroy (H.R. 1961) that would turn the Saver’s Credit into a refundable credit. If your potential Saver’s Credit exceeds your tax liability for the year, the taxpayers give you a refund anyway—although “refund” is a poor choice of words, since the dollars would come from other taxpayers.

What is the point of drawing a bright line at your tax liability? Opponents of refundable credits call it welfare, since the refundable part comes from other taxpayers. If you limit the credit to tax liability, it’s easier to characterize it as a tax reduction. (“Welfare,” “tax reduction.” Words are really loaded, aren’t they?) Proponents of refundable credits note the arbitrary nature of the line that’s being drawn at the taxpayer’s tax liability. If she’s engaging in the favored activity that generates the credit, why draw a line at her tax liability? Particularly as the complexity of the Tax Code, with all its other deductions, exemptions and credits, makes that line increasingly arbitrary.

It’s instructive to note what other credits in the Tax Code are refundable. What activities are so favored by Congress that they are willing to have other taxpayers support the activity? The big one is the earned income credit, which constitutes taxpayer help for the working poor. There are also a couple of narrowly targeted credits aimed at farmers with high fuel costs and some unemployed individuals who need help with their health insurance costs. Most other credits—the child tax credit, adoption assistance, dependent care, the list is a long one—are nonrefundable. Congress just hates stepping over that line.

So what do I think? (Actually, nobody really asked me, but I have the floor.) I favor making the Saver’s Credit refundable. In my view, helping low income workers save for their retirement falls into the same category as the earned income credit for the working poor. They’re doing everything society wants and encourages them to do, yet often through no fault of their own they need help making ends meet. They’re exactly the ones the rest of us, through our tax dollars, ought to encourage, assist and support. They're the productive ones, the good guys.

Besides, if you look at the way the Tax Code is structured, you get the definite sense that deductions and credits serve fundamentally different purposes. Deductions are generally aimed at figuring the "right" measure of your ability to pay income tax. Credits, on the other hand, are designed to encourage specific activities; they are not germane to calculating your fair share of the country's overall need for tax revenue.

So what do you think? I’d like to know. Send me an email at TheTwoLeggedStool@gmail.com. Or, better, post a comment.

Which leads me to focus on one particular feature of the Saver's Credit: it’s a nonrefundable credit. That’s tax jargon for a credit that is limited to your tax liability. A nonrefundable credit can only operate to reduce your tax liability. If your potential credit is a dollar more than your tax liability, you don’t get that extra dollar.

There’s currently a bill recently introduced into the House of Representatives by Congressman Pomeroy (H.R. 1961) that would turn the Saver’s Credit into a refundable credit. If your potential Saver’s Credit exceeds your tax liability for the year, the taxpayers give you a refund anyway—although “refund” is a poor choice of words, since the dollars would come from other taxpayers.

What is the point of drawing a bright line at your tax liability? Opponents of refundable credits call it welfare, since the refundable part comes from other taxpayers. If you limit the credit to tax liability, it’s easier to characterize it as a tax reduction. (“Welfare,” “tax reduction.” Words are really loaded, aren’t they?) Proponents of refundable credits note the arbitrary nature of the line that’s being drawn at the taxpayer’s tax liability. If she’s engaging in the favored activity that generates the credit, why draw a line at her tax liability? Particularly as the complexity of the Tax Code, with all its other deductions, exemptions and credits, makes that line increasingly arbitrary.

It’s instructive to note what other credits in the Tax Code are refundable. What activities are so favored by Congress that they are willing to have other taxpayers support the activity? The big one is the earned income credit, which constitutes taxpayer help for the working poor. There are also a couple of narrowly targeted credits aimed at farmers with high fuel costs and some unemployed individuals who need help with their health insurance costs. Most other credits—the child tax credit, adoption assistance, dependent care, the list is a long one—are nonrefundable. Congress just hates stepping over that line.

So what do I think? (Actually, nobody really asked me, but I have the floor.) I favor making the Saver’s Credit refundable. In my view, helping low income workers save for their retirement falls into the same category as the earned income credit for the working poor. They’re doing everything society wants and encourages them to do, yet often through no fault of their own they need help making ends meet. They’re exactly the ones the rest of us, through our tax dollars, ought to encourage, assist and support. They're the productive ones, the good guys.

Besides, if you look at the way the Tax Code is structured, you get the definite sense that deductions and credits serve fundamentally different purposes. Deductions are generally aimed at figuring the "right" measure of your ability to pay income tax. Credits, on the other hand, are designed to encourage specific activities; they are not germane to calculating your fair share of the country's overall need for tax revenue.

So what do you think? I’d like to know. Send me an email at TheTwoLeggedStool@gmail.com. Or, better, post a comment.

Labels:

Public Policy,

Savings Buckets

Friday, April 24, 2009

The Saver’s Credit

Your federal government wants you to save for your own retirement. In fact, they want it so much they are willing to give you a matching contribution of sorts. But only if you have low income. In other words, you can get a reward for saving only if you are too poor to afford to save. Oh well.

Notwithstanding that Catch 22, there are plenty of people who can afford to save for retirement and who meet the requirements to benefit. Here are the ground rules.

• This governmental benefit comes in the form of a tax credit. It’s not an actual matching contribution, in that it’s not added to your retirement account, like your employer’s 401(k) match. Rather, it comes to you in the form of reduced income tax liability (or an increased refund) come April 15. So your tax credit ought to free up an equivalent number of other dollars, enabling you to increase the amount you otherwise were able to contribute to a retirement plan. Economically, the tax credit can act just like a matching contribution. That’s the theory anyway.

• The tax credit is not a refundable credit. That means it is limited to no more than your income tax liability for the year. Unfortunately, this takes a lot of low-income people out of the running.

• You become entitled to the credit by contributing to a tax-favored retirement plan of some kind, either an Individual Retirement Account, a Roth IRA, or your own contribution to a 401(k) plan, 403(b) Plan, 457 Plan, or SIMPLE IRA Plan.

• The maximum contribution that’s matched is $2,000 per year.

• The credit percentage, or matching percentage if you will, is based on your Adjusted Gross Income. The lower your Adjusted Gross Income, the higher your matching percentage. It starts out at a healthy 50% match if your AGI (in 2009) is under $16,500 ($33,000 if married), and ratchets down to 10% if your AGI is under $27,750 ($55,500 if married). AGI above those amounts, and you’re out of luck. No credit for you!

• To avoid abuses, your contribution that otherwise entitles you to a tax credit is reduced by any recent distributions you took from a retirement plan—during the year of your contribution or the following year up to the due date of your tax return, or either of the two preceding years.

• To avoid even sneakier abuses, your matched contribution is also reduced by recent retirement plan distributions taken by your spouse. They’re up to your tricks, you rascal.

• Those under age 18, full time students, and those claimed by a parent as a dependent cannot qualify for the saver’s credit.

• You claim the credit by filing a Form 8880 with your tax return.

If you meet all these requirements, you have extra reasons to strive to put away a little something for the future.

Notwithstanding that Catch 22, there are plenty of people who can afford to save for retirement and who meet the requirements to benefit. Here are the ground rules.

• This governmental benefit comes in the form of a tax credit. It’s not an actual matching contribution, in that it’s not added to your retirement account, like your employer’s 401(k) match. Rather, it comes to you in the form of reduced income tax liability (or an increased refund) come April 15. So your tax credit ought to free up an equivalent number of other dollars, enabling you to increase the amount you otherwise were able to contribute to a retirement plan. Economically, the tax credit can act just like a matching contribution. That’s the theory anyway.

• The tax credit is not a refundable credit. That means it is limited to no more than your income tax liability for the year. Unfortunately, this takes a lot of low-income people out of the running.

• You become entitled to the credit by contributing to a tax-favored retirement plan of some kind, either an Individual Retirement Account, a Roth IRA, or your own contribution to a 401(k) plan, 403(b) Plan, 457 Plan, or SIMPLE IRA Plan.

• The maximum contribution that’s matched is $2,000 per year.

• The credit percentage, or matching percentage if you will, is based on your Adjusted Gross Income. The lower your Adjusted Gross Income, the higher your matching percentage. It starts out at a healthy 50% match if your AGI (in 2009) is under $16,500 ($33,000 if married), and ratchets down to 10% if your AGI is under $27,750 ($55,500 if married). AGI above those amounts, and you’re out of luck. No credit for you!

• To avoid abuses, your contribution that otherwise entitles you to a tax credit is reduced by any recent distributions you took from a retirement plan—during the year of your contribution or the following year up to the due date of your tax return, or either of the two preceding years.

• To avoid even sneakier abuses, your matched contribution is also reduced by recent retirement plan distributions taken by your spouse. They’re up to your tricks, you rascal.

• Those under age 18, full time students, and those claimed by a parent as a dependent cannot qualify for the saver’s credit.

• You claim the credit by filing a Form 8880 with your tax return.

If you meet all these requirements, you have extra reasons to strive to put away a little something for the future.

Labels:

Savings Buckets

Thursday, April 23, 2009

Roth Accounts for Federal Employees?

Riddle: What does a Roth 401(k) account have to do with smoking cigarettes?

Answer: Read on.

I am a big fan of Roth savings, as expressed in a number of prior posts; particularly for those who would like to save more in their tax-favored retirement plans, but are prevented from doing so because of limitations in the Tax Code. So Roth 401(k) accounts, potentially available since 2006, have been a great recent development, since they carry no income-related restrictions. But Roth 401(k) accounts are only an option if your employer chooses to make them available.

What about federal employees? Federal employees are covered by the Thrift Savings Plan, a 401(k)-like retirement savings plan. Unfortunately, there is no provision for Roth accounts in the Thrift Savings Plan, so federal employees are out of luck.

But that may change soon. The Board governing the Thrift Savings Plan has this week endorsed a proposal to add a Roth option to the TSP. That’s the good news. Now here’s the bad news: actually adding such a feature requires legislation. The House of Representatives passed a bill adding Roth accounts to the TSP, but the Senate and President also have to act.

Now back to the riddle: What does Roth saving have to do with cigarette smoking? In the real world, nothing. In Bizarro congressional world, apparently they are deeply related in ways the rest of us can’t begin to fathom. The provision for adding a Roth savings option to the TSP is included in a bill to give the FDA authority to regulate tobacco. So whether federal employees get a favorable retirement saving opportunity may hinge on how your senator feels about giving the FDA the power to regulate tobacco.

Federal employees, join the rest of us. We in private industry only get Roth opportunities if our employers choose to add it to our 401(k) plans; you only get them if your senator believes in federal regulation of tobacco.

Answer: Read on.

I am a big fan of Roth savings, as expressed in a number of prior posts; particularly for those who would like to save more in their tax-favored retirement plans, but are prevented from doing so because of limitations in the Tax Code. So Roth 401(k) accounts, potentially available since 2006, have been a great recent development, since they carry no income-related restrictions. But Roth 401(k) accounts are only an option if your employer chooses to make them available.

What about federal employees? Federal employees are covered by the Thrift Savings Plan, a 401(k)-like retirement savings plan. Unfortunately, there is no provision for Roth accounts in the Thrift Savings Plan, so federal employees are out of luck.

But that may change soon. The Board governing the Thrift Savings Plan has this week endorsed a proposal to add a Roth option to the TSP. That’s the good news. Now here’s the bad news: actually adding such a feature requires legislation. The House of Representatives passed a bill adding Roth accounts to the TSP, but the Senate and President also have to act.

Now back to the riddle: What does Roth saving have to do with cigarette smoking? In the real world, nothing. In Bizarro congressional world, apparently they are deeply related in ways the rest of us can’t begin to fathom. The provision for adding a Roth savings option to the TSP is included in a bill to give the FDA authority to regulate tobacco. So whether federal employees get a favorable retirement saving opportunity may hinge on how your senator feels about giving the FDA the power to regulate tobacco.

Federal employees, join the rest of us. We in private industry only get Roth opportunities if our employers choose to add it to our 401(k) plans; you only get them if your senator believes in federal regulation of tobacco.

Labels:

Roth Savings,

Savings Buckets

Wednesday, April 22, 2009

Longevity Risk and Market Risk

Yesterday’s post made a point about saving up a sufficient amount to meet your retirement needs. And the point was this: that in a world of many uncertainties, the uncertainty of how the financial markets will treat all of us exceeds the uncertainty of how long your particular lifespan will be.

And today’s point is this: So what! You have to live with both uncertainties. You don’t get to choose one or the other.

There is a silver lining of sorts: The financial risk of an extra-long life is presumably independent of the risk of an extra-crummy market environment. (Then again, maybe they’re not independent. Maybe suffering through a bad market environment makes you want to die. I know it’s making me pretty sick.)

Assuming they are unrelated, your true financial risk is that you will suffer through both bad situations simultaneously. This point was made by Messrs. Blanchett and Blanchett in the article discussed in January 14’s post. (I shouldn’t refer to long life as bad. Long life is generally a good thing. It’s just the financial aspect of it that’s bad.)

How does this affect Goldilocks from yesterday’s post? If she saves enough to meet her projected needs for an average life expectancy in an average market environment, she actually has about a 75% chance of not running out of money while still alive. That’s not too bad. (Caveat: These percentages incorrectly use the historical performance of the financial markets to measure the likelihood of future success. It's wrong to do that, but I do it anyway. Like eating potato chips.)

Unfortunately, Goldilocks gains only diminishing returns in her level of certainty as she increases her savings. For example, building up her retirement savings by an additional 30% gets her from a 75% up to about an 88% chance of not outliving her life retirement savings.

Don’t you just hate uncertainty?

And today’s point is this: So what! You have to live with both uncertainties. You don’t get to choose one or the other.

There is a silver lining of sorts: The financial risk of an extra-long life is presumably independent of the risk of an extra-crummy market environment. (Then again, maybe they’re not independent. Maybe suffering through a bad market environment makes you want to die. I know it’s making me pretty sick.)

Assuming they are unrelated, your true financial risk is that you will suffer through both bad situations simultaneously. This point was made by Messrs. Blanchett and Blanchett in the article discussed in January 14’s post. (I shouldn’t refer to long life as bad. Long life is generally a good thing. It’s just the financial aspect of it that’s bad.)

How does this affect Goldilocks from yesterday’s post? If she saves enough to meet her projected needs for an average life expectancy in an average market environment, she actually has about a 75% chance of not running out of money while still alive. That’s not too bad. (Caveat: These percentages incorrectly use the historical performance of the financial markets to measure the likelihood of future success. It's wrong to do that, but I do it anyway. Like eating potato chips.)

Unfortunately, Goldilocks gains only diminishing returns in her level of certainty as she increases her savings. For example, building up her retirement savings by an additional 30% gets her from a 75% up to about an 88% chance of not outliving her life retirement savings.

Don’t you just hate uncertainty?

Labels:

Retirement Spending Plan

Tuesday, April 21, 2009

Longevity Risk vs. Market Risk

Words matter. The words that are used to describe something color—even distort—how we think about that thing, and can easily mislead us.

I read an article about a retired person’s risk of running out of money before she runs out of pulse. Financial professionals call that “longevity risk.” What I don’t like about those words is the connotation that running out of savings during retirement is somehow your fault. You chose to live too long, you selfish Baby Boomer. It’s not something that happened to you, it’s something you brought on your own damn self. Or maybe it’s your parents’ fault for bequeathing you such sturdy genes. Where’s George Carlin when we need him?

But the risk of living too long is minor compared to the risk of living through a crummy market environment. And the market environment is not something you brought on yourself, like healthy living; it’s something that’s thrust upon you (and all your classmates) by the accident of when you reached retirement age. 1926? A great year to retire. 1969? Terrible.

In what way is market risk greater than longevity risk? Here’s a little fairy tale.

Goldilocks has turned 65 and is about to retire. She needs for her savings to generate $50,000 per year, plus inflation. She has saved up $649,271, which, it turns out, is just right if she lives an average female life expectancy (which at age 65 is 20 years) and retires in an average market environment.

But wait! Goldilocks is smarter than that. Despite the bear thing, which happened when she was very young, so it doesn’t count. She realizes she might live longer than average. So to be cautious, she magically increases her savings to $849,006. (This is a fairy tale, so she can do that.) That’s the amount she’ll need if she lives to age 98, which only 5% of 65-year-old women are expected to do. (These projections came from a table of life expectancy statistics on the Social Security website.) So by increasing her savings by $200,000 she is 95% sure not to get stung by longevity risk.

But wait! What about market risk? Goldilocks prudently plans to invest her savings 50% in stocks and 50% in bonds. What if the upcoming future for stock returns, bond returns and inflation is worse than the historical average? It turns out that market risk is much scarier than longevity risk. Goldilocks studies 83 20-year periods from 1926 through 2008 and sees that during 10 of them—more than 15% of the time—her extra $200,000 of extra savings would have been an insufficient cushion; she would have run out of bucks before the end of her average 20 year life expectancy.

Goldilocks's extra $200,000 of savings bought her 95% certainty of avoiding longevity risk, but only 85% certainty of dodging market risk.

It turns out that market risk—the one that’s shared by you and everyone who got the gold watch in the same year—is bigger than longevity risk—the one that’s unique to you. And 2008 turned out to herald a very inauspicious start for the current crop of graduating retirees. Can you just picture a whole cohort of 65-year olds, eyes glazed over, all wandering around Miami Beach at 4:30, all looking for the same early bird special?

I read an article about a retired person’s risk of running out of money before she runs out of pulse. Financial professionals call that “longevity risk.” What I don’t like about those words is the connotation that running out of savings during retirement is somehow your fault. You chose to live too long, you selfish Baby Boomer. It’s not something that happened to you, it’s something you brought on your own damn self. Or maybe it’s your parents’ fault for bequeathing you such sturdy genes. Where’s George Carlin when we need him?

But the risk of living too long is minor compared to the risk of living through a crummy market environment. And the market environment is not something you brought on yourself, like healthy living; it’s something that’s thrust upon you (and all your classmates) by the accident of when you reached retirement age. 1926? A great year to retire. 1969? Terrible.

In what way is market risk greater than longevity risk? Here’s a little fairy tale.

Goldilocks has turned 65 and is about to retire. She needs for her savings to generate $50,000 per year, plus inflation. She has saved up $649,271, which, it turns out, is just right if she lives an average female life expectancy (which at age 65 is 20 years) and retires in an average market environment.

But wait! Goldilocks is smarter than that. Despite the bear thing, which happened when she was very young, so it doesn’t count. She realizes she might live longer than average. So to be cautious, she magically increases her savings to $849,006. (This is a fairy tale, so she can do that.) That’s the amount she’ll need if she lives to age 98, which only 5% of 65-year-old women are expected to do. (These projections came from a table of life expectancy statistics on the Social Security website.) So by increasing her savings by $200,000 she is 95% sure not to get stung by longevity risk.

But wait! What about market risk? Goldilocks prudently plans to invest her savings 50% in stocks and 50% in bonds. What if the upcoming future for stock returns, bond returns and inflation is worse than the historical average? It turns out that market risk is much scarier than longevity risk. Goldilocks studies 83 20-year periods from 1926 through 2008 and sees that during 10 of them—more than 15% of the time—her extra $200,000 of extra savings would have been an insufficient cushion; she would have run out of bucks before the end of her average 20 year life expectancy.

Goldilocks's extra $200,000 of savings bought her 95% certainty of avoiding longevity risk, but only 85% certainty of dodging market risk.

It turns out that market risk—the one that’s shared by you and everyone who got the gold watch in the same year—is bigger than longevity risk—the one that’s unique to you. And 2008 turned out to herald a very inauspicious start for the current crop of graduating retirees. Can you just picture a whole cohort of 65-year olds, eyes glazed over, all wandering around Miami Beach at 4:30, all looking for the same early bird special?

Labels:

Retirement Spending Plan

Monday, April 20, 2009

The Better Investor Savings Bucket

There are many nice tax savings features of tax-favored retirement accounts—Individual Retirement Accounts, Roth IRA’s, 401(k) Plans, etc. And I’ve written a large number of posts about them. One of the subtler benefits of tax-favored retirement accounts compared to taxable investment accounts is how they make you a better investor.

Think about it. When you have your savings in a taxable investment account, the income tax consequences taints every investment move you make (or neglect to make).

• You tend to prefer tax-exempt municipal bonds over treasury or corporate bonds—so you don’t have to pay federal income tax on the interest.

• You tend to prefer your own state’s municipal bonds over your neighboring state’s, so you don’t have to pay state income tax on the interest.

• You tend to prefer stocks over bonds so you can benefit from temporarily tax-free appreciation and lower-taxed capital gain instead of taxable interest.

• You tend to prefer growth stocks over dividend-paying stocks for the same reasons.

• You tend to hold onto stocks that have substantially appreciated to avoid triggering a whopping capital gain.

• For the same reason, you tend to avoid rebalancing your mix of stocks and bonds to get back to your desired asset allocation.

• You tend to hold onto recently purchased stocks for longer than you might otherwise wish so you can turn high-taxed short-term gain into low-taxed long-term gain.

• As you age, you tend to hold onto highly appreciated stocks so your family can benefit from the increase in tax basis that occurs at death. Which some days feels like it’s just around the corner, doesn't it?

• When your stocks lose value, you tend to sell them prematurely for no other reason than to benefit from the tax losses.

All of these distortions in your thinking and acting just melt away when your investments are in a tax-favored retirement account. The shelter of its tax-exemption allows you to make the right investment decisions untainted by extraneous tax consequences. Goodness knows it’s hard enough to do that without the Tax Code breathing down your neck.

Think about it. When you have your savings in a taxable investment account, the income tax consequences taints every investment move you make (or neglect to make).

• You tend to prefer tax-exempt municipal bonds over treasury or corporate bonds—so you don’t have to pay federal income tax on the interest.

• You tend to prefer your own state’s municipal bonds over your neighboring state’s, so you don’t have to pay state income tax on the interest.

• You tend to prefer stocks over bonds so you can benefit from temporarily tax-free appreciation and lower-taxed capital gain instead of taxable interest.

• You tend to prefer growth stocks over dividend-paying stocks for the same reasons.

• You tend to hold onto stocks that have substantially appreciated to avoid triggering a whopping capital gain.

• For the same reason, you tend to avoid rebalancing your mix of stocks and bonds to get back to your desired asset allocation.

• You tend to hold onto recently purchased stocks for longer than you might otherwise wish so you can turn high-taxed short-term gain into low-taxed long-term gain.

• As you age, you tend to hold onto highly appreciated stocks so your family can benefit from the increase in tax basis that occurs at death. Which some days feels like it’s just around the corner, doesn't it?

• When your stocks lose value, you tend to sell them prematurely for no other reason than to benefit from the tax losses.

All of these distortions in your thinking and acting just melt away when your investments are in a tax-favored retirement account. The shelter of its tax-exemption allows you to make the right investment decisions untainted by extraneous tax consequences. Goodness knows it’s hard enough to do that without the Tax Code breathing down your neck.

Labels:

Investments,

Savings Buckets

Sunday, April 19, 2009

Your Teenager’s Retirement Saving

Teenagers. Ya gotta love ‘em. It’s like having your own personal Linda Blair around the house. As long as you’ve got to get yourself and your kids through the high maintenance teenage years, you might as well impart some good habits along the way. Like acceptable hygiene. And retirement saving.

When they get that first summer or after-school job, they are going to have a lot of discretionary income—a lot compared to what they need and are used to. So there’s no better time than the teenage years for them to begin the saving habit—setting aside a portion of their working income in a savings bucket of one kind or another. Saving is like playing baseball or doing crossword puzzles or lifting weights or playing guitar—the more you do it, the better you get at it. It becomes second nature. So there’s no better time for a person to learn how to save than when she has her first taste of discretionary compensation.

You might even encourage your kids’ saving habit by subsidizing it. Maybe give them a dollar for every two they put away in a savings bucket, so they can continue to enjoy some of the consumption benefits of their hard-earned income. It’ll be like your own family matching contribution.

So what’s the best kind of savings bucket for a teenager? That’s a no-brainer. It’s the Roth IRA! Teenagers don’t have much income (except for Miley Cyrus) so they usually meet the qualification rules for contributing to a Roth IRA, as described in February 4’s post. And for a teenager, the tax cost of foregoing a deduction (had they instead contributed to a traditional IRA) is very small; maybe even zero. Then the dollars they put aside—and every dollar of investment earnings for the next 70 or 80 years—is totally tax-free. What a deal!

Now don’t you wish you were a teenager again so that you could start your own Roth IRA? When I was a teenager there was no such thing as IRA's or Roth IRA's. Or electricity. Or the wheel.

When they get that first summer or after-school job, they are going to have a lot of discretionary income—a lot compared to what they need and are used to. So there’s no better time than the teenage years for them to begin the saving habit—setting aside a portion of their working income in a savings bucket of one kind or another. Saving is like playing baseball or doing crossword puzzles or lifting weights or playing guitar—the more you do it, the better you get at it. It becomes second nature. So there’s no better time for a person to learn how to save than when she has her first taste of discretionary compensation.

You might even encourage your kids’ saving habit by subsidizing it. Maybe give them a dollar for every two they put away in a savings bucket, so they can continue to enjoy some of the consumption benefits of their hard-earned income. It’ll be like your own family matching contribution.

So what’s the best kind of savings bucket for a teenager? That’s a no-brainer. It’s the Roth IRA! Teenagers don’t have much income (except for Miley Cyrus) so they usually meet the qualification rules for contributing to a Roth IRA, as described in February 4’s post. And for a teenager, the tax cost of foregoing a deduction (had they instead contributed to a traditional IRA) is very small; maybe even zero. Then the dollars they put aside—and every dollar of investment earnings for the next 70 or 80 years—is totally tax-free. What a deal!

Now don’t you wish you were a teenager again so that you could start your own Roth IRA? When I was a teenager there was no such thing as IRA's or Roth IRA's. Or electricity. Or the wheel.

Labels:

Retirement Planning,

Roth Savings,

Savings Buckets

Saturday, April 18, 2009

Planning for Disclaimers

In a few recent posts, I have described how disclaimers work, and how they can be used by your beneficiary after your death to reroute your retirement benefits. Like most things, disclaimers work best if your planning has been done before your death, rather than afterward. And like most things, planning works best if you’ve talked to your loved ones, and have a good idea of what they might want.

Here are a few variations:

• The original idea was mentioned by noted retirement expert Ed Slott, and described in April 15’s post. It is also the most common. Here is a recap: You name your spouse as primary beneficiary, with your children, equally per stirpes, as contingent beneficiaries. Then if you die (actually, not “if” but “when”), if your spouse does not feel she needs your entire retirement account, she can disclaim a portion and that portion then goes to your children.

• The disclaimers don’t have to stop there. If one of your children is then feeling equally magnanimous, he can also disclaim a portion of his share, and the disclaimed portion will go to his children—your beloved grandchildren, they should live and be well. (An aside: This highlights the importance of ensuring that you write your Beneficiary Designation Form so that if a child predeceases you, his share goes to his kids and not his siblings. That’s the import of using the words “per stirpes.”)

• If your primary beneficiary (your spouse, say) has a charitable bent, you can name her favorite charity as contingent beneficiary. Then to the extent she disclaims, the retirement account goes to her favorite charity. That is often a tax efficient way to get dollars from a traditional retirement account to a charity.

• If your family is wealthy enough to be concerned about estate taxes (you lucky dog!), you can name your spouse as primary beneficiary with a trust for your spouse as contingent beneficiary. Then by disclaiming a portion, your spouse can cause your estate to take better advantage of the $3,500,000 estate tax exemption. And she can still benefit from the trust! What a country!

• If your family is wealthy enough to be hit by estate taxes, be sure your Will has a clause that allocates additional estate taxes that might be caused by a disclaimer to the branch of the family benefiting from the disclaimer. Fair’s fair.

So talk to your family. Before you die; not afterward.

Here are a few variations:

• The original idea was mentioned by noted retirement expert Ed Slott, and described in April 15’s post. It is also the most common. Here is a recap: You name your spouse as primary beneficiary, with your children, equally per stirpes, as contingent beneficiaries. Then if you die (actually, not “if” but “when”), if your spouse does not feel she needs your entire retirement account, she can disclaim a portion and that portion then goes to your children.

• The disclaimers don’t have to stop there. If one of your children is then feeling equally magnanimous, he can also disclaim a portion of his share, and the disclaimed portion will go to his children—your beloved grandchildren, they should live and be well. (An aside: This highlights the importance of ensuring that you write your Beneficiary Designation Form so that if a child predeceases you, his share goes to his kids and not his siblings. That’s the import of using the words “per stirpes.”)

• If your primary beneficiary (your spouse, say) has a charitable bent, you can name her favorite charity as contingent beneficiary. Then to the extent she disclaims, the retirement account goes to her favorite charity. That is often a tax efficient way to get dollars from a traditional retirement account to a charity.

• If your family is wealthy enough to be concerned about estate taxes (you lucky dog!), you can name your spouse as primary beneficiary with a trust for your spouse as contingent beneficiary. Then by disclaiming a portion, your spouse can cause your estate to take better advantage of the $3,500,000 estate tax exemption. And she can still benefit from the trust! What a country!

• If your family is wealthy enough to be hit by estate taxes, be sure your Will has a clause that allocates additional estate taxes that might be caused by a disclaimer to the branch of the family benefiting from the disclaimer. Fair’s fair.

So talk to your family. Before you die; not afterward.

Labels:

Estate Planning

Friday, April 17, 2009

Rules Governing Disclaimers

In yesterday’s post, I described the consequences of disclaiming your entitlement to receive a retirement account left to you by a recently deceased person—a spouse, a parent, whatever. “Well,” you might be thinking, “this could be useful. How do I do one of those disclaimer things?” As might be expected, there are plenty of requirements to meet. Here is a summary of them.

1. The disclaimer has to be an unqualified refusal to accept the property. You can’t reserve the right to change your mind.

2. The disclaimer has to apply to either the entire property or to a fractional part of it. For example, if someone has named you beneficiary of an IRA, you can keep 75% of it and disclaim your right to 25% of it.

3. The disclaimer must be in writing.

4. The writing must be delivered to the transferor of the property. In the case of a retirement account, that means the trustee or custodian of the account.

5. The written disclaimer must be delivered no later than nine months after the decedent’s death (or nine months after you turn 21, if later).

6. You must not have accepted any benefit from the property. There’s some leeway here. In a magnanimous ruling the IRS said that if all you took from an IRA is the required minimum distribution for the year of the decedent’s death, it’s still not too late to disclaim the rest of the IRA. Nonetheless, this particular requirement can easily trip you up. It might mean, for example, that you had better not take control of the retirement account’s investments if you are later going to disclaim. Who knows?

7. As a result of the disclaimer, the property must pass to the ultimate recipient without any direction from you. That means you don’t get to say who gets it; that’s determined by the decedent (now, alas, gone to his reward) based on the way he wrote his Beneficiary Designation Form.

8. You cannot benefit from the disclaimed property. For example, if you are the primary beneficiary of your parent’s IRA, and the contingent beneficiary is a trust under which you are also a beneficiary, then the disclaimer won’t qualify. In order to make it work, you would have to disclaim your rights under the trust as well as disclaiming your rights under the IRA. This particular rule doesn’t apply to surviving spouses; but it applies to all other types of beneficiaries.

9. Your disclaimer has to meet all the requirements of your state’s laws governing disclaimers.

So those are the ground rules in a nutshell. Pretty tricky, huh? That’s why it’s important to get a competent knowledgeable lawyer involved whenever you venture into disclaimer world.

1. The disclaimer has to be an unqualified refusal to accept the property. You can’t reserve the right to change your mind.

2. The disclaimer has to apply to either the entire property or to a fractional part of it. For example, if someone has named you beneficiary of an IRA, you can keep 75% of it and disclaim your right to 25% of it.

3. The disclaimer must be in writing.

4. The writing must be delivered to the transferor of the property. In the case of a retirement account, that means the trustee or custodian of the account.

5. The written disclaimer must be delivered no later than nine months after the decedent’s death (or nine months after you turn 21, if later).

6. You must not have accepted any benefit from the property. There’s some leeway here. In a magnanimous ruling the IRS said that if all you took from an IRA is the required minimum distribution for the year of the decedent’s death, it’s still not too late to disclaim the rest of the IRA. Nonetheless, this particular requirement can easily trip you up. It might mean, for example, that you had better not take control of the retirement account’s investments if you are later going to disclaim. Who knows?

7. As a result of the disclaimer, the property must pass to the ultimate recipient without any direction from you. That means you don’t get to say who gets it; that’s determined by the decedent (now, alas, gone to his reward) based on the way he wrote his Beneficiary Designation Form.

8. You cannot benefit from the disclaimed property. For example, if you are the primary beneficiary of your parent’s IRA, and the contingent beneficiary is a trust under which you are also a beneficiary, then the disclaimer won’t qualify. In order to make it work, you would have to disclaim your rights under the trust as well as disclaiming your rights under the IRA. This particular rule doesn’t apply to surviving spouses; but it applies to all other types of beneficiaries.

9. Your disclaimer has to meet all the requirements of your state’s laws governing disclaimers.

So those are the ground rules in a nutshell. Pretty tricky, huh? That’s why it’s important to get a competent knowledgeable lawyer involved whenever you venture into disclaimer world.

Labels:

Estate Planning

Thursday, April 16, 2009

About Disclaimers

In yesterday’s post, I described an idea for how your heirs can utilize a disclaimer after your death. I don’t usually like to write about death in this retirement planning forum; it's just not seemly. But I suppose it’s appropriate for me to summarize the ground rules governing disclaimers. Someone has to do it. Here goes.

What is a disclaimer? Imagine you are entitled to receive something as a result of someone else’s death—a bequest; a house; life insurance proceeds; a retirement account; whatever. Now imagine—and this is the hard part—you don’t want it. You can simply refuse to accept it, and then it goes to the next person in line, just as if you had died before your benefactor. That’s a disclaimer.

If the disclaimer is handled properly, then for tax purposes it’s treated as if you had never been entitled to the property in the first place. It’s treated as if the deceased person had instead left it to the ultimate recipient instead of you. If the property is a retirement account, like an IRA, here’s what that means:

• Most significantly, the ultimate recipient, and not you, becomes entitled to the account. Duh.

• The ultimate recipient, and not you, pays income tax on distributions (unless it’s a Roth account). That could be a good thing for the family if the ultimate recipient is in a lower tax bracket as typically happens when he is one or two generations younger.

• The ultimate recipient’s life expectancy governs required minimum distributions, rather than yours. That would enhance the tax deferral benefits of the retirement account if the ultimate recipient is a generation or two younger than you.

• The estate tax consequences of the retirement account are determined as if the account was left directly to the ultimate recipient. (The import of that statement will just have to wait for another day.)

So that’s it in a nutshell. Tomorrow’s post will summarize the ground rules for properly implementing a disclaimer.

What is a disclaimer? Imagine you are entitled to receive something as a result of someone else’s death—a bequest; a house; life insurance proceeds; a retirement account; whatever. Now imagine—and this is the hard part—you don’t want it. You can simply refuse to accept it, and then it goes to the next person in line, just as if you had died before your benefactor. That’s a disclaimer.

If the disclaimer is handled properly, then for tax purposes it’s treated as if you had never been entitled to the property in the first place. It’s treated as if the deceased person had instead left it to the ultimate recipient instead of you. If the property is a retirement account, like an IRA, here’s what that means:

• Most significantly, the ultimate recipient, and not you, becomes entitled to the account. Duh.

• The ultimate recipient, and not you, pays income tax on distributions (unless it’s a Roth account). That could be a good thing for the family if the ultimate recipient is in a lower tax bracket as typically happens when he is one or two generations younger.

• The ultimate recipient’s life expectancy governs required minimum distributions, rather than yours. That would enhance the tax deferral benefits of the retirement account if the ultimate recipient is a generation or two younger than you.

• The estate tax consequences of the retirement account are determined as if the account was left directly to the ultimate recipient. (The import of that statement will just have to wait for another day.)

So that’s it in a nutshell. Tomorrow’s post will summarize the ground rules for properly implementing a disclaimer.

Labels:

Estate Planning

Wednesday, April 15, 2009

Retirement Accounts and Disclaimers

In yesterday’s post, I mentioned a TV show I saw on PBS presented by Ed Slott, noted authority on retirement planning. Buried in the two-hour show was a little gem of advice about leaving your retirement accounts to your kids. Here it is in a nutshell.

As I’ve mentioned before in March 20’s post, it’s almost inevitable that your children will inherit some meaningful retirement assets from you. Why? Because with all of life’s uncertainties, it’s hard to die broke. So whatever’s left usually goes to the kids.

But what if things go well for you, and after the first spouse dies, the surviving spouse feels like she’s got more than enough to sustain her for the rest of her life? Then the surviving spouse can make the decision to leave the deceased spouse’s retirement accounts—or some appropriate fraction of them—to the kids. How? By executing a proper “disclaimer.” What’s that, you ask. It’s a refusal to take what’s coming to her as a result of the death of her spouse. Then the disclaimed property goes to the next in line, which, if you’ve set it up properly, is the kids.

If your surviving spouse is feeling flush, and wants the kids to get a little inheritance today, rather than waiting for the next death, your retirement accounts make an excellent vehicle for this largesse. Why? Because with their longer life expectancies, they can turbo-charge the tax benefits of your retirement accounts, as pointed out in March 20’s post.

How do you set up this play for your surviving spouse and children? It turns out it’s not only easy, but it fits well with what you’re no doubt planning to do anyway: Name your spouse as your primary beneficiary on the Beneficiary Designation Form that comes along with your retirement accounts. In the space for “contingent beneficiary” (you know, the person who gets the dough if your named primary beneficiary has predeceased you), name your children equally per stirpes. Then when the grim reaper comes for you, your spouse (the one you really want to provide for) can accept her inheritance; or if she feels she can afford it, she can disclaim part of it and allow the kids to enjoy part of their inheritance while they’re in their high-maintenance years. Thanks for the good idea, Ed.

But wait, there’s more! What if one of your kids is also feeling pretty flush and would rather his inheritance goes to his own children, your grandchildren? Your child can also execute a disclaimer, allowing all or a part of his inherited retirement account to pass just as if he too had predeceased you. Then it goes to his kids. With their very long life expectancies, the value of those retirement accounts just got bigger. (See March 21’s post.) A good idea just got even better!

And the beauty of it is that the decision is not made by you today, but rather by those who survive you, and therefore have better knowledge of whether they can afford to be generous.

A word of caution. Disclaimers are tricky, and must be executed properly and promptly (within nine months of death) for them to work. So be sure your survivors consult with a competent and knowledgeable lawyer before trying to implement this idea. I know, you’d rather stick your left thumb in a wood chipper than get a lawyer involved, but this is an area where that’s the prudent thing to do. I mean involving a lawyer.

As I’ve mentioned before in March 20’s post, it’s almost inevitable that your children will inherit some meaningful retirement assets from you. Why? Because with all of life’s uncertainties, it’s hard to die broke. So whatever’s left usually goes to the kids.

But what if things go well for you, and after the first spouse dies, the surviving spouse feels like she’s got more than enough to sustain her for the rest of her life? Then the surviving spouse can make the decision to leave the deceased spouse’s retirement accounts—or some appropriate fraction of them—to the kids. How? By executing a proper “disclaimer.” What’s that, you ask. It’s a refusal to take what’s coming to her as a result of the death of her spouse. Then the disclaimed property goes to the next in line, which, if you’ve set it up properly, is the kids.

If your surviving spouse is feeling flush, and wants the kids to get a little inheritance today, rather than waiting for the next death, your retirement accounts make an excellent vehicle for this largesse. Why? Because with their longer life expectancies, they can turbo-charge the tax benefits of your retirement accounts, as pointed out in March 20’s post.

How do you set up this play for your surviving spouse and children? It turns out it’s not only easy, but it fits well with what you’re no doubt planning to do anyway: Name your spouse as your primary beneficiary on the Beneficiary Designation Form that comes along with your retirement accounts. In the space for “contingent beneficiary” (you know, the person who gets the dough if your named primary beneficiary has predeceased you), name your children equally per stirpes. Then when the grim reaper comes for you, your spouse (the one you really want to provide for) can accept her inheritance; or if she feels she can afford it, she can disclaim part of it and allow the kids to enjoy part of their inheritance while they’re in their high-maintenance years. Thanks for the good idea, Ed.

But wait, there’s more! What if one of your kids is also feeling pretty flush and would rather his inheritance goes to his own children, your grandchildren? Your child can also execute a disclaimer, allowing all or a part of his inherited retirement account to pass just as if he too had predeceased you. Then it goes to his kids. With their very long life expectancies, the value of those retirement accounts just got bigger. (See March 21’s post.) A good idea just got even better!

And the beauty of it is that the decision is not made by you today, but rather by those who survive you, and therefore have better knowledge of whether they can afford to be generous.

A word of caution. Disclaimers are tricky, and must be executed properly and promptly (within nine months of death) for them to work. So be sure your survivors consult with a competent and knowledgeable lawyer before trying to implement this idea. I know, you’d rather stick your left thumb in a wood chipper than get a lawyer involved, but this is an area where that’s the prudent thing to do. I mean involving a lawyer.

Labels:

Estate Planning

Tuesday, April 14, 2009

Ed Slott’s Retirement Planning Advice

This is hard to believe, but I saw a TV show about retirement planning. Not only that, but it was two hours long. Not only that, but it was on a PBS station. Not only that, but it was shown as part of their annual pledge drive to get you to send them some dough. You’d think they would show reruns of Simon and Garfunkel in Central Park from 25 years ago; but, no, instead it was a lecture by noted authority Ed Slott on securing your retirement. (Thanks to my friend Denis who alerted me to the show, so I could DVR it and skip over the pledge parts.)

Of course, it’s hard to convey lots of good little ideas in a two-hour mass-audience TV show, but he did an excellent job of summarizing the big picture:

• Know where you stand;

• Educate yourself about your options;

• Get good advice;

• Take the long view;

• Take action in small consistent steps.

You’ve got to agree with him on these recommendations.